CHOOSE YOUR POISON: THE SNP’S CURRENCY HEADACHE

26 April 2019

In an important new paper, Sam Taylor explains how the SNP’s currency proposals overlook Scotland’s balance of payments position, which makes its plan to continue using the pound outside of a formal monetary union untenable. Furthermore, the same issue means that an independent Scotland’s only other option – its own currency – is not the panacea some more radical supporters of independence have suggested.

“This is an important and timely paper. There is much misunderstanding, misinformation and indeed ignorance on what would be an appropriate currency regime choice for an independent Scotland. Many seem to think that by defining a wish list on the currency issue that that is how the issue is settled. However, in a world of trillions of dollars of foreign exchange transactions each and every day, moving freely to capture maximum returns, the only test of a currency regime is whether it is credible to international capital. As this paper clearly demonstrates, neither of the proposals advocated by proponents of independence would meet that test and both are simply a recipe for a speculative attack, which would be hugely disruptive and costly to the Scottish economy.”

Professor Ronald MacDonald – Research Professor of Macroeconomics and International Finance, University of Glasgow

A pdf version of this paper can be downloaded here.

Executive Summary

The 2019 SNP conference will be asked to make a critical decision about the party’s manifesto for independence. The currency question was arguably decisive in 2014, and it remains the issue which most vexes supporters of Scottish independence.

Whether or not the SNP has a credible answer on currency is fundamental to its entire project. A failure to be straight with the Scottish people will have electoral consequences which could cost it the chance of ever delivering indyref2, let alone winning it.

Delegates are being told they face a choice between pragmatism and a panacea. Between the thin gruel of the Growth Commission’s wait and see approach, and the radical optimism of an independent Scotland with its own currency from day one. On the surface, these two plans seem very different. The reality, which this paper will explain, is that they are far more alike than the proponents of either would care to acknowledge.

The Growth Commission’s proposals are not nearly as pragmatic as it thinks. And a new currency, particularly if Scotland attempts to peg its value against the pound, has many of the same painful consequences as the Growth Commission plan. Neither can escape the implications of Scotland’s balance of payments position.

The SNP wants people to believe that Scotland’s own currency will happen after a “business as usual” transition period of continued use of the pound, otherwise known as sterlingisation. Sterlingisation is emphatically not “business as usual”. It places Scotland beyond the supervisory reach of the Bank of England, with limited access to sterling reserves – an unstable and ultimately untenable arrangement.

Scotland could embark on independence with its own currency, but a 1-1 peg against the pound would be very short lived – insufficient foreign exchange reserves would leave the new currency at the mercy of international capital markets. Scotland could not defend its value.

In both cases the endgame is the same: Scotland has a new currency which is worth less than sterling, and ordinary households pay the price. Imports and mortgages are more expensive, wages and state pensions are less valuable. The Government is saddled with an Annual Solidarity Payment denominated in pounds sterling. More competitive exports is scant consolation.

Anyone lucky enough to be mortgage-free and with significant assets denominated in pounds sterling (such as a private pension) would be quite comfortable. But the average homeowner, or the pensioner reliant on a state pension, would be very badly hurt.

This is a point worth remembering the next time someone tells you that Scottish independence is about achieving social justice. An independent Scotland is certainly possible – but it would come at an immense cost.

“That from and after the Union the Coin shall be of the same standard and value throughout the United Kingdom as now in England…” (Act of Union, 1707)

“What happens with respect to currency the day before an independence vote would happen the day after and continue to happen until such time as the elected Scottish Government seeks to do something differently.” (Sustainable Growth Commission, 2018)

Background

Should Scotland use a different currency to the rest of the United Kingdom? For 307 years this was not a question which excited much interest, even amongst supporters of Scottish independence. The answer was clear, and in Scotland’s Future, the 2013 White Paper setting out its manifesto for independence, the SNP proposed a formal monetary union with the UK. If it voted for independence, Scotland would continue to use sterling within a framework supervised by the Bank of England (over which Scotland would retain some influence).

But there was a problem: the UK Government flatly rejected the idea of a formal monetary union. The ‘No’ vote in 2014 convinced the SNP that it could not afford to fight another independence referendum with a currency plan which relied on the assent of the UK Government.

The Sustainable Growth Commission was established by the SNP in 2016, to update Scotland’s Future, and a credible currency plan would be one of its most important challenges.

It proved to be an insurmountable one. When, in 2018, its report was finally published, the Growth Commission had replaced the uncertainties of 2014 with a currency plan including more questions than answers. (In fact, six questions and no answers.)

The Growth Commission called for an independent Scotland to continue to use sterling, but without the benefits of a formal monetary union – a plan colloquially referred to as sterlingisation. The report unconvincingly attempted to reject the label, stating: “This option is not ‘sterlingisation’ (since Scotland already uses Sterling)”1Sustainable Growth Commission report [C1.10]

This is semantics: the plan is sterlingisation in every substantive respect, and the Scottish Government’s own Fiscal Commission used exactly that label when it dismissed the idea back in 2013:

“As an aside, there is the option for Scotland to adopt Sterling through an informal process of ‘sterlingisation’. While this option would retain some of the benefits of a formal monetary union there would also be some additional drawbacks. In this instance, the Scottish Government would have no input into governance of the monetary framework and only limited ability to provide liquidity to the financial sector - this would depend on the resources and reserves of the country. The amount of currency available would depend almost entirely on the strength of the Scottish Balance of Payments position.”2Fiscal Commission Working Group - First Report - Macroeconomic Framework. February 2013 (page 125)

What had changed between 2013 and 2018? If sterlingisation was a bad idea then, isn’t it still a bad idea today? The Fiscal Commission’s remark about “the Scottish Balance of Payments position” is extremely significant, and a topic to which this paper will return.

The Growth Commission knew that sterlingisation would be a profoundly unsatisfactory arrangement for an independent Scotland, so it had to suggest a way out. It did this by teasing the possibility of Scotland establishing its own currency, but only once six tests had been met:3Sustainable Growth Commission report [3.212]

-

Fiscal sustainability: Has the Scottish Government sustainably secured its fiscal policy objectives and sufficiently strong and credible fiscal position, in relation to budget deficit and overall debt level?

-

Central Bank credibility and stability of debt issuance: Has the Scottish Central Bank and Government framework established sufficient international and market credibility evidenced by the price and the stability of the price of its debt issuance?

-

Financial requirements of Scottish residents and businesses: Would a separate currency meet the on-going needs of Scottish residents and businesses for stability and continuity of their financial arrangements and command wide support?

-

Sufficiency of foreign exchange and financial reserves: Does Scotland have sufficient reserves to allow currency management?

-

Fit to trade and investment patterns: Would the new arrangement better reflect Scotland’s new and developing trading or investment patterns?

-

Correlation of economic and trade cycle: Is the economic cycle in Scotland significantly out of phase with that of the rest of the UK, or at least as well correlated with the cycles of other trading and investment partners, thus making an independent monetary policy feasible and desirable?

How long might it be before an independent Scotland could pass the six tests and establish its own currency? The Growth Commission dodged this question in a number of different ways:

“Will an Independent Scotland Adopt a Distinct Scottish Currency? Not in the short to medium term. The Scottish Government should commit to retaining sterling for an extended transition period.” [C4.17]

“Given the need for a transition period, the need to build institutional capacity and the timescales associated with establishing fiscal credibility (see the recommendations in Part B of this report), we anticipate that these six tests are unlikely to be met until towards the end of the first decade following a successful independence vote. However, it is possible that we have underestimated the economy’s growth performance and potential and it will occur more quickly.” [C2.8]

“The arrangements supporting the Scottish currency and the Scottish financial system should enable the Scottish Government to choose to establish a separate currency at a future date. However, this should not be taken an indication of any commitment to do so.” [C2.2]

So: it won’t be soon, it might be in around 10 years, or it could be never.

This obfuscation was not popular with SNP members. During a series of National Assemblies, many argued that the policy of a post-independence SNP Government should be to establish Scotland’s own currency as soon as possible. This convinced the party leadership to offer a concession. Announced via a front page splash in The National4Revealed: The SNP WILL propose a new currency for an independent Scotland. The National. 1st March 2019, the SNP promised a quicker transition to a Scottish currency, with a vote to decide the matter inside the first post-independence parliament.

But this concession quickly unravelled. It was little more than smoke and mirrors. Far from resolving the obfuscation, it added yet more: the motion to be put before the SNP conference recommends that a newly created Scottish Central Bank should report annually to parliament on progress towards passing the six tests, with an aspiration to vote on establishing a Scottish currency within the first parliament.5Poundland, Robin McAlpine. Bella Caledonia. 2nd March 2019

A commitment to keep checking on progress is not a commitment to making progress.

The six tests are unpopular with SNP members because they are either painful or impossible.

Much of the debate over the Growth Commission has been around the challenge of meeting tests 1-3, which focus on fiscal credibility and economic stability. The report accepted that this would mean getting Scotland’s fiscal deficit to below 3% of GDP and recognised that this would require severe spending restraint.

In short: the Growth Commission implicitly endorsed austerity and recognised that an independent Scotland would need much more of it. This did not impress supporters of independence who would rather not accept “the neoliberal consensus” (a consensus to which the EU is, of course, committed).

Tests 1-3 are doable, but painful.

Test 4 demands that Scotland must have “sufficient” foreign exchange reserves. Foreign exchange reserves can only be accumulated by running a consistent fiscal or trade surplus. That means brutal austerity, going way beyond the Growth Commission’s plans, or a radical upending of Scotland’s terms of trade6The terms of trade is the relative price of imports in terms of exports and is defined as the ratio of export prices to import prices., which is not credible while Scotland is using sterling.

Tests 5 and 6 both depend on Scotland decoupling in a meaningful way from the UK’s economy, which is hardly likely to happen whilst monetary policy is outsourced to the Bank of England.

Tests 4-6 are a Catch-22. They are effectively impossible.

Why did the SNP settle on such an unsatisfactory currency plan? Andrew Wilson has been remarkably frank about what motivated the Growth Commission. Speaking to the BBC’s Douglas Fraser on Good Morning Scotland (7th April 2019), Wilson said of the Growth Commission:

“My sole motivation in many of these arguments, which feel like they are a challenge to the orthodoxy – that are different – is about trying to grow a consensus – to win middle ground people over to the case for Scottish independence.”7BBC Good Morning Scotland, 7th April 2019

Sterlingisation is a bad idea. But that didn’t matter to Andrew Wilson. It was the kind of bad idea that might just persuade “middle ground people” to vote for independence, and that was the only thing that really mattered.

Sterlingisation: a compromised compromise

Sterlingisation has obvious flaws, and flaws that are less obvious, but no less important.

The Growth Commission could not avoid the question of monetary policy:

“We recognise that this means that the Scottish Government would not secure monetary policy sovereignty in the initial period following an independence vote…”8Sustainable Growth Commission report [C1]

But it did avoid perhaps the most critical issue of all: an independent Scotland’s balance of payments position (recall that the Scottish Government’s own Fiscal Commission highlighted this back in 2013).

The Growth Commission report runs to 354 pages, but “balance of payments” is mentioned just four times. Each of those mentions is this exact same passage of text:

“Improved data and analysis: There are gaps in the data that are available on Scotland’s trade balance, and on the wider balance of payments position which should be addressed in the short [sic] so that the evidence is available on which decisions on policy and assessments of its success can be based. This is an immediate priority.”9Sustainable Growth Commission report [3.98 no.20, A6.46, A6.214, A7.1 no.20]

This was no doubt true when the report was written, but by the time the it was published (after repeated delays) improved data was available, and what it tells us is hugely important.

The balance of payments

The balance of payments statement records a country’s cross border transactions, and it has two distinct parts.

-

Current transactions, such as imports and exports, are recorded in the current account.

-

Capital transactions, such as the sale of stocks or bonds to foreigners, are recorded in the capital account (which is sometimes called the financial account).

The two parts must balance. Deficits on the current account must be financed by inflows on the capital account (meaning that foreigners are building up financial claims on the country).

Conversely, a current account surplus means that a country is sending capital abroad, and building up financial claims on the rest of the world.

The Scottish data

The current account has three components: net trade (exports minus imports), net primary income (earnings on foreign investments minus domestic earnings owned by foreign investors), and net transfers (generally a negligible item).

New improved data on Scotland’s net trade10The Scottish Government: Development of Supply & Use Satellite Accounts for Extra- Regio Economic Activities. 22nd February 2018 and net primary income11The Scottish Government: Development of a Primary Income Account and Gross National Income (GNI) for Scotland. 2nd May 2018 positions was published in February 2018 and May 2018 respectively (before the May 2018 publication of Growth Commission report, albeit only a few days before with the net primary income data). The net primary income data was subsequently updated again in December 2018.12The Scottish Government: Development of a Primary Income Account and Gross National Income (GNI) for Scotland, 19th December 2018

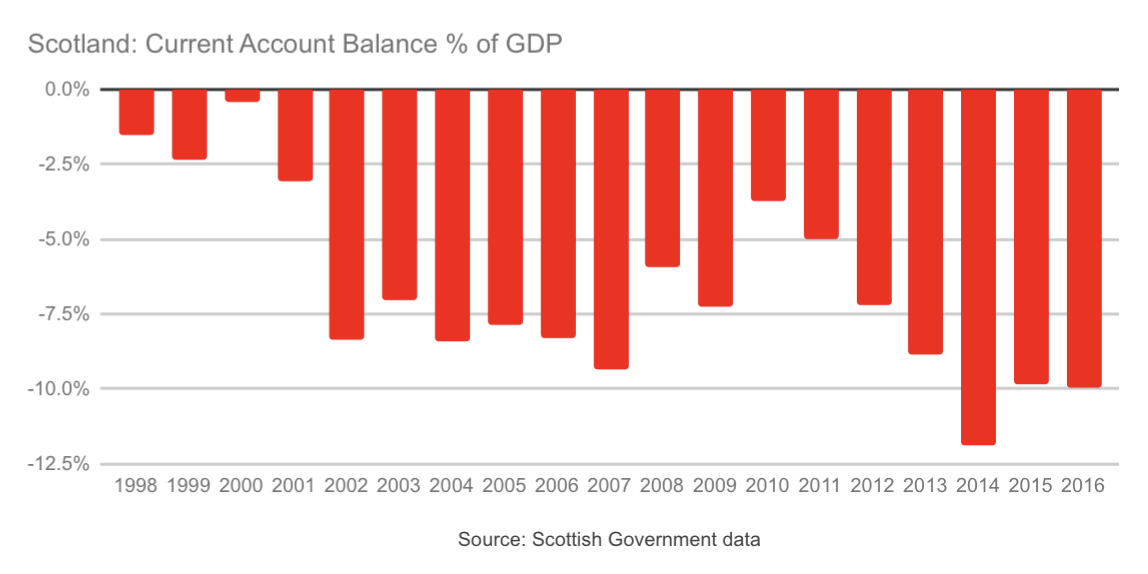

The data (which allocates Scotland a geographic share of North Sea activity, and treats rUK as a foreign country) revealed that Scotland’s current account deficit was -£15.9 billion, or -10% of GDP, in 2016 (the latest year for which data is available) divided roughly equally between net trade and net primary income. (For reference, the UK current account deficit is about -4% of GDP, also split roughly equally between net trade and net primary income).13Balance of Payments. ONS website.

The inclusion of North Sea activity has a positive impact on net trade, but this is substantially offset by a negative impact on net primary income, since most of the assets in the North Sea are owned by companies outside of Scotland.

This chart shows the current account balance as a percentage of GDP over the period for which data is available. Notably, even when the oil price was above $100/bbl, Scotland’s current account balance was consistently in a deficit position, and over recent years has averaged around -10% of GDP.

Why is this important?

For a country with its own currency, a current account deficit should not be thought of as a gap that needs plugging. It’s really just an accounting record of monetary transactions between the domestic and the foreign sector.

Unless a country has substantial foreign exchange reserves to run down, when goods or services are imported, a foreigner ends up holding its currency. It might not be the exporter that ends up holding it – the foreign exchange market means it could be anyone – but it is someone.

Now, if we pretend that physical money doesn’t exist (which for cross border transactions is more or less true – importers don’t typically pay in cash) then that currency still exists within the domestic banking system. It’s the only place it can exist.

Currency flows out via the current account and back in via the capital account simultaneously and automatically.

Whether it just sits in a bank account, or is spent on purchasing stocks or bonds or real physical assets, doesn’t much matter – it has not escaped the country – it just belongs to foreigners now.

But all of this is true if, and only if, a country is using its own currency. The situation is fundamentally different if another country’s currency is used.

An independent sterlingised Scotland paying for imports in pounds could not automatically expect those pounds to flow back in via the capital account. The natural place for pounds sterling to be is in the UK banking system.

Scotland would be fighting a constant battle to prevent its banking system running short of sterling.

It’s important to clarify what this means. It does not mean that Scottish banks, or Scottish households and businesses, are losing money in a profit & loss sense.

A banking system depends on reserves to function. Reserves are a bank’s most liquid assets – notes and coins count, but so do special accounts held with the central bank – and they are essential to ensure the smooth running of the payments system. If a bank does not have sufficient reserves, it cannot function. Customers cannot withdraw money, or make payments.

Scotland’s banking system would be running short of sterling reserves.

Normally, a central bank stands permanently ready to provide sufficient reserves to its banking system. Those reserves have a price – that’s how central banks influence interest rates – but they are always available in whatever quantity is required.

But a sterlingised independent Scotland has chosen to place itself beyond the supervisory reach of the Bank of England. The Growth Commission is admirably frank about the consequences of this:

“It is likely that the result would be that some companies would move their domicile to England in response, in expectation of broader support from the Bank of England. This is in any event logical, since regardless of the location of the registered offices of RBS and Lloyds Banking Group, a substantial part of the executive functions of these banks is already exercised in London. Indeed most, if not all, of the banks have already made clear in public statements that they would be headquartered in London for the purposes of regulation in the event of independence.”14Sustainable Growth Commission report [C3.28]

The Growth Commission appears to envision a Scotland in which the current Scottish banking infrastructure becomes branch offices of UK banks, with a distinctively Scottish system developing in parallel. The latter would have no access to Bank of England reserves, and the former would depend on UK commercial banks operating as a conduit between Scotland and the Bank of England – an unstable arrangement, and a strange kind of independence.

This is the difference between a formal monetary union and sterlingisation. A formal monetary union would have kept Scotland under direct Bank of England supervision. Sterlingisation is not basically the same as a monetary union, it is fundamentally different.

Scotland’s twin deficits (fiscal and current account) mean that it would have to sell sterling denominated bonds at high enough rates of interest to attract substantial quantities of sterling into Scotland.

This is the classic recipe for a currency crisis: foreigners demand ever higher rates, as Scotland’s financial position becomes ever more precarious.

Eventually this becomes unsustainable. Scotland would have to adopt its own currency as a matter of necessity.

The “six tests” are actually a red herring. They give the impression that an orderly transition from sterlingisation to Scotland’s own currency is possible. In fact, Scotland would eventually be forced to adopt its own currency, whatever the six tests might be saying.

This is not scaremongering. Recall what the Scottish Government’s own Fiscal Commission had to say about sterlingisation in 2013:

“The amount of currency available would depend almost entirely on the strength of the Scottish Balance of Payments position.”15Fiscal Commission Working Group - First Report - Macroeconomic Framework. February 2013 (page 125)

The Fiscal Commission was right, and this issue has not disappeared because the Growth Commission chose to ignore it.

Why is it unavoidable?

There are really only two ways to avoid this outcome.

If Scotland embarked on independence with a huge war chest of sterling reserves, it might be able to get away with being sterlingised for an extended period. But those reserves do not exist.

Alternatively, if some creative way could be found to attract sterling flows – other than paying exorbitant rates of interest – then that might work. This is how Panama gets away with being dollarised and running a consistent current account deficit: it is a tax haven, and sucks in dollars looking to hide from the IRS. Needless to say, this is not a model that would find favour with the typical supporter of Scottish independence.

Anyone tempted to argue that Scotland will simply adjust its current account position to get around the problem must consider what that actually means.

Net primary income is not something which can be adjusted at will, at least not legally. And a trade deficit is a sticky thing. A country cannot just magic up huge quantities of additional exports. Curbing imports is easier, but if the choice is between abandoning sterlingisation or imposing rationing, then it's pretty clear that sterlingisation must collapse.

How would households be impacted?

What would the end of sterlingisation mean for a typical Scottish household?

The Growth Commission set out a vision for a distinct Scottish retail banking system, outside the regulatory supervision of the Bank of England.

The report is candid about the constraints that sterlingisation would impose on the new Scottish Central Bank (SCB) in its ability to provide “lender of last resort” support to the Scottish banking system. The Growth Commission acknowledges that only the ring-fenced retail activities of Scottish banks could be supported.16Sustainable Growth Commission report [C3.25 & C3.26]

It accepts that this would mean the redomicile of most of the pre-existing Scottish financial sector to England. The report also includes this remarkable statement: “During the independence referendum in 2014 the charge was made that an independent Scotland could not afford to ‘bail-out’ banks deemed too big to fail. Given all of the above, this charge is no longer relevant.” The charge is only “no longer relevant” because the Growth Commission has pleaded guilty to it.17Sustainable Growth Commission report [C3.28]

Even the very limited financial support which the SCB would offer under sterlingisation is not credible. A state with its own currency can offer a cast-iron deposit guarantee because, in extremis, it can always create the money needed to back deposits. This option would not be available to the SCB, and the Growth Commission acknowledges this by suggesting that it might be necessary to borrow the money needed to make depositors whole.18Sustainable Growth Commission report [C3.27]

This is fanciful. Scotland would already be borrowing sterling at very high rates. In a crisis severe enough that banks were failing, the idea that it could just borrow even more sterling to protect depositors is not remotely credible.

This uncomfortable fact would encourage a significant proportion of Scots to keep (and/or move) deposits into the UK banking system, to benefit from the Bank of England’s deposit guarantee. This would also exacerbate Scotland’s balance of payments problem, and accelerate the collapse of sterlingisation.

For people who had kept what they thought were safe sterling deposits in the new Scottish banking system, the collapse of sterlingisation would mean those deposits were at risk of forcible redenomination into the new currency, whilst those who had moved deposits into the UK system would still be holding balances guaranteed to remain in pounds sterling.

The new currency would have to be worth less than sterling to alleviate the balance of payments problem, so redenomination would be a painful experience. But that pain would fall disproportionately on the poorest (since they would be the least likely to have sterling assets in the UK).

Scotland’s own currency: no panacea

With a formal monetary union off the table, and sterlingisation unsustainable, an independent Scotland’s only other option is its own currency (joining the euro might be a very long term aspiration, but Scotland’s own currency would have to come first).

But Scotland’s own currency is by no means a panacea.

If Scotland established its own currency in an orderly fashion, during a transition to independence, it would almost certainly attempt to peg its value 1-1 with the pound, to minimise disruption.

With a 1-1 peg, Scotland would still effectively be shadowing Bank of England monetary policy, and it would still have the same balance of payments position, and depend on annual capital inflows of around 10% of GDP.

The difference is that those inflows are now denominated in Scotland’s own currency. If it’s a free-floating currency (that is its value can move freely against other currencies) then its market price will automatically adjust to that price at which supply and demand for the new currency are in equilibrium. There is no magic involved – that is just what a market price is, by definition.

But if the currency is pegged, it cannot float freely. The central bank has to intervene to ensure that supply and demand are in equilibrium at a predetermined price.

This is an asymmetric problem. If demand for the currency exceeds supply, a central bank can always create an increased supply of its currency to keep a lid on the exchange rate. But if supply exceeds demand, the central bank needs a war chest of foreign currency reserves in order to intervene and create the extra demand required to support the exchange rate.

An independent Scotland requiring inflows of 10% of GDP annually would certainly be in the latter category. This is why, if Scotland wanted to peg its brand new currency 1-1 with the pound, it would require very substantial foreign exchange reserves.

�

Shortcuts to FX reserves do not exist

Scotland could expect to receive around £10 billion of foreign exchange reserves as a population share of the UK’s holdings19HM Treasury. Exchange Equalisation Account: report and accounts 2017-18, and might hope to accumulate a few billion more through households exchanging sterling notes and coins for new Scottish currency. The total would certainly be less than the 2016 current account deficit.

How much would be enough? There is no hard and fast number, but Growth Commission chair Andrew Wilson put Scotland’s predicament starkly into perspective when he outlined his thinking in a recent column for The National:

“However, Denmark still holds around $70 billion in currency reserves compared to the UK at $164bn with Scotland’s share of that around $13bn20Note that Wilson’s $13bn is the USD equivalent of the £10bn mentioned previously. or less than a fifth of Denmark’s level and around half of Bulgaria’s. We could borrow to build that up which wouldn’t add to net debt because the borrowed money would be on our balance sheet as an asset, at least until we had to trade its value to defend our currency. But borrowing such vast sums, with added currency risk on top of deficit funding we would inherit from the UK, before we had properly established ourselves, would be very expensive indeed.”21Andrew Wilson: Everyone will benefit if we fix gender pay gap. The National. 7th March 2019

Wilson’s suggestion that Scotland would need somewhere between double and five times the quantity of FX reserves it would actually have is not unreasonable, although he misses the fact that this is no less true under sterlingisation. And he is right to pour cold water on the idea of borrowing to plug the gap.

In fact, the borrowing idea is even more dangerous than he admits. Asking financial markets to lend you the foreign currency needed to prop up the value of your currency simply advertises the weakness of your position.

Speculators will respond by borrowing the vulnerable currency to purchase those foreign exchange reserves, which makes a precarious currency even more vulnerable (you’re back to square one, but with increased foreign currency debt).

The dangerous borrowing idea is included in a paper published by Common Weal: Backing Scotland’s Currency – Foreign exchange reserves for an Independent Scotland.22Common Weal: Backing Scotland’s Currency – Foreign exchange reserves for an Independent Scotland. Peter Ryan. June 2017 It also includes another proposal: that the Scottish Central Bank and the Bank of England would establish swap lines giving Scotland access to substantial sterling reserves.

Broadly speaking there are two kinds of central bank swap lines: the first is designed to ease global liquidity at times of financial stress, and the second is for the purpose of promoting orderly foreign exchange markets, typically with key trading partners. The Federal Reserve has a useful page explaining the principles.23Central bank liquidity swaps, Federal Reserve website

It seemed to me that Common Weal had made a serious error in conflating these two very different types of arrangement. This suspicion was confirmed when I contacted its Head of Policy and Research, Craig Dalzell, to ask him what exactly the paper was proposing. He pointed me towards a Bank of England working paper on liquidity swaps24Bank of England Staff Working Paper No. 741 Central bank swap lines. Saleem Bahaj & Ricardo Reis. July 2018, which is quite explicit that the mechanisms it describes could not be used for foreign exchange interventions (page 6):

“As important as what they do and what risks they entail, is what the swap lines are not. First, they are not direct exchange rate interventions. Central bank swap lines have been used in the past, especially during the Bretton Woods regime, as a way to obtain the foreign currency needed to sustain a peg. Yet, with the modern swap lines, the source-country currency is not used right away to buy recipient-country currency and prop up its price.”

To be absolutely sure, I contacted the Bank of England staffers who wrote the working paper for clarification. This was their reply:

“As discussed in the Staff Working Paper, the swap lines between central banks in their current guise have not been used directly for exchange rate stabilisation. They are a liquidity facility for commercial banks. A different institutional framework would be required if their purpose were to change.”

The swap lines envisioned in the Common Weal paper have exchange rate stabilisation in mind, and the closest analogue is therefore the North American Framework Arrangement (NAFA) swap lines established in 1994 between the Federal Reserve and Canada ($2 billion) and the Federal Reserve and Mexico ($3 billion).

The Canadian facility has never been used, and the Mexican one was last used in 1995 when Mexico was suffering the effects of a full blown currency crisis.25The ‘Tequila Crisis’

The Bank of England and a future Scottish Central Bank might well come up with a similar arrangement to the NAFA swap lines, but it would be a standby measure for use in an emergency, and could not credibly be used as an upfront way to generate FX reserves.

Craig Dalzell acknowledged, by email, that I was right about this, but Common Weal has never published any kind of correction, and continues to push the paper as part of its campaign to persuade people that Scotland establishing its own currency would be relatively painless.

The author of the Common Weal paper, Peter Ryan, wrote a piece for The National in June 2017, headlined: Prophets of doom claim our currency would collapse ... it’s important to set record straight.26Peter Ryan: Prophets of doom claim our currency would collapse ... it’s important to set record straight, The National, 22nd June 2017

It included this remark on the central bank swap line proposal:

“These methods are all commonly used by central banks all over the world to ensure the stability of their currency.”

This is categorically false.

It is an inescapable fact that Scotland would embark on independence with woefully inadequate FX reserves. In the context of a -10% of GDP current account deficit, defending a 1-1 peg against the pound would be impossible, and the peg would very quickly be broken, leading to a depreciation in the value of the new Scottish currency against sterling.

This would be very painful indeed for households. The price of imports would rise, and liabilities (such as mortgages) denominated in pounds sterling would become much more expensive to service (since Scottish workers would be paid in the weaker new currency).

A weaker currency does mean more competitive exports, but that would be scant consolation to the typical household.

The Mortgage Credit Directive

Mortgages are legal contracts between the bank and the borrower. Homeowners with pre-existing mortgages in a post-independence Scotland would find that they still owed the bank sterling.

This is another area where Common Weal has spread misinformation, attempting to persuade voters that a pain-free independence for Scotland is possible.

How To Launch a Scottish Currency – Preparing Scotland for monetary sovereignty from day one of independence27Common Weal: How To Launch a Scottish Currency – Preparing Scotland for monetary sovereignty from day one of independence. Craig Dalzell & Peter Ryan. 20th August 2018, was co-authored by Peter Ryan and Craig Dalzell, and published in August 2018. It includes these reassuring words on how banks will be legally required to mitigate the currency risk of sterling denominated mortgages (page 3):

“Schemes may be put in place to ensure a smooth transition for people with liabilities currently denominated in Sterling. An example already established in UK law is the Mortgage Credit Directive which mandates that banks must offer protections to customers whose mortgage is denominated in a currency other than the currency of the user’s income or residence (at the moment, this is usually aimed at customers who own homes outside of the UK). Measures mandated by the MCD include measures are in place to limit the risk that customers become exposed to changes in exchange rate up to and including giving customers the right to redenominate their mortgage into an alternative currency. [sic] Similar measures could be introduced to support other debts or liabilities such as pensions.”

The suggestion here is that mortgages contracted under UK law give the borrower the legal right (via the Mortgage Credit Directive) to redenominate in an alternative currency, in the event that they are receiving income in a different currency to the mortgage.

This, however, is not correct. The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority is unambiguous on this point:

“Under the MCOB (Mortgage Conduct Of Business) rules, the regulatory status of a mortgage is set at the time the agreement is entered into. So if a customer starts getting paid in a different currency after they take out a mortgage, the firm should only treat the mortgage as a foreign-currency loan if the customer enters into a new mortgage contract.”28Foreign-currency lending. FCA website

It could hardly be any clearer: the Mortgage Credit Directive only applies to mortgages denominated in a foreign currency “at the time the agreement is entered into”.

Homeowners in an independent Scotland with pre-existing sterling denominated mortgages would not have a legal right to redenominate, and Common Weal should not be misleading people in this way.

The Annual Solidarity Payment

The Growth Commission proposes that an independent Scotland should negotiate an Annual Solidarity Payment with the UK, and suggests £5.3 billion is an appropriate figure.29Sustainable Growth Commission report [B4.38]

This comprises £3 billion in debt servicing contributions, £1.3 billion in foreign aid (which the UK would administer on Scotland’s behalf) and £1 billion for other shared services.

Scotland’s contribution to debt interest payments is based on it assuming responsibility for a population share of the UK Government’s borrowing, less a population share of the value of certain assets that would remain with the UK.

The exact figure would be a matter for negotiation, but one thing is for sure: whatever the number, the UK would demand payment in pounds sterling.

It has been argued by some that the legal principle of lex monetae, which says that a sovereign state has the unilateral right to redenominate its external obligations, could be used by Scotland to convert its share of UK debt into its own currency.

However, this principle applies to states with their own currency, redenominating liabilities in that currency. It could not be used by Scotland in a bilateral negotiation with the UK.

In a 2016 paper for Common Weal: How to make a Currency – A Practical Guide30Common Weal: How to make a Currency – A Practical Guide. Peter Ryan. 31st December 2016, Peter Ryan suggested that Scotland could use the lex monetae argument to redenominate its share of the UK debt, but almost immediately admitted that the idea is legally nonsensical (page 10):

“However this interpretation would be open to legal challenge in the case of UK debt which had been apportioned to Scotland following independence (as the debt would be expressly denominated in Sterling and the currency of the continuing UK is still Sterling).”

Conclusion

The Growth Commission’s sterlingisation plan is unsustainable. Its collapse as a result of Scotland’s banking system running short of sterling reserves would be inevitable, and force an independent Scotland to adopt its own currency in the worst possible circumstances.

Scotland could embark on independence with its own currency, but a 1-1 peg against the pound would be very short lived – insufficient foreign exchange reserves would leave the new currency at the mercy of international capital markets. Scotland could not defend its value.

In truth, the two alternatives are not really very different: they just represent alternative ways to swallow the same bitter pill.

Sterlingisation inevitably leads to redenomination and devaluation.

Independence with Scotland’s own currency means the same things, but in a more orderly fashion: redenomination happens first, with devaluation soon afterwards.

In both cases the endgame is the same: Scotland has a new currency which is worth less than sterling, and ordinary households pay the price. Imports and mortgages are more expensive, wages and state pensions are less valuable. The Government is saddled with an Annual Solidarity Payment denominated in pounds sterling. More competitive exports is scant consolation.

Anyone lucky enough to be mortgage-free and with significant assets denominated in pounds sterling (such as a private pension) would be quite comfortable. But the average homeowner, or the pensioner reliant on a state pension, would be very badly hurt.

This is a point worth remembering the next time someone tells you that Scottish independence is about achieving social justice. An independent Scotland is certainly possible – but it would come at an immense cost.

Please log in to create your comment