12 PORTS: SOUTHAMPTON – THE INVISIBLE SEA

20 April 2019

The first of a series of pieces following Jonathan Winter and his boat, Nova, on a voyage around Britain and Ireland. Dr Matt Kerr, Lecturer in British Literature from 1837 to 1939 at the University of Southampton, writes about Southampton and ‘The Invisible Sea’.

This essay is about not seeing the sea. Or about how to see the sea while not seeing it, taking as a particular case study Southampton in the nineteenth century. By the Victorian period, Southampton’s primary boast as a port was the speed with which things might depart from it—the city called itself the ‘Gateway to Empire’, and it was part of its attractiveness that goods and people could move through without friction. Fruit arriving from South Africa in the morning could be in London markets by afternoon. It is indicative that, when the railway came to Southampton in the 1840s, a tunnel was built from the ports, under the city, to the station so that gold bullion arriving from mines abroad could pass through the city without ever touching it.

Things might once have gone another way. Southampton was always a valuable sea port, in part because of the harbour’s unique double tide, which is why legend suggests it as the place where King Cnut sat when making his vain attempt to hold back the waves. But, at the turn of the nineteenth century, Southampton seemed to offer more than a convenient point of entry or departure. In fact, John Feltham’s A Guide to All the Watering and Sea-bathing Places (1803) emphasized the variety of Southampton’s attractions. Southampton was, Feltham claimed, ‘Equally adapted for health, pleasure, and commerce’, ‘uncommonly striking’, and ‘almost unparalleled in the beauty of its features’. Such mixed purposes could be an advantage: precisely this combination of pleasure and commerce drew Jane Austen and her family, for example, to Southampton between 1806 and 1809, when the port was both fashionable and close enough to Portsmouth that her brother Frank could commute to work, as it were, in the Navy.

Even for Feltham, though, Southampton seemed to lack something.

As a sea-bathing place, indeed, it has less reputation than some others that are described in this work. It has no machines, nor is its beach favorable for immersion; the marine is, also, deeply mixed with the fresh water. . . . The air is soft and mild, and sufficiently impregnated with saline particles to render it agreeable, and even salutary, to those who cannot endure a full exposure to the sea, on a bleak and open shore.

The sea at Southampton isn’t quite the sea, its ‘saline particles’ attenuated by the riverine atmosphere. The shift in register toward the end of this passage indicates that Southampton’s aesthetics are, for Feltham, as mixed up as its atmosphere and water—instead of ‘full’ exposure to marine sublimity, only a partial one is available, with the ‘bleak and open shore’ adulterated by the miscellaneousness of Southampton’s commitments to the sea. The initial comprehensiveness of Feltham’s praise turns out to be a mixed blessing.

Compare the impressions of another Romantic visitor. The Isle of Wight, just off Southampton Water, was the scene of composition of Keats’s sonnet ‘On the Sea’ (1817), which begins, ‘It keeps eternal whisperings around / Desolate shores’, and enjoins the reader midway through: ‘O ye! who have your eye-balls vexed and tired, / Feast them on the wideness of the Sea’. In fact, it may have been Southampton itself that ‘vexed and tired’ Keats: when he visited Southampton on the way to the Isle of Wight, he found little to hold his interest.

I know nothing of this place but that it is long—tolerably broad—has bye streets—two or three Churches—a very respectable old Gate with two Lions to guard it. The Men and Women do not materially differ from those I have been in the Habit of seeing. . . . The Southampton water when I saw it just now was no better than a low Water Water which did no more than answer my expectations.

Distant aesthetically, if not literally, from the bracing caverns and shores of the Isle of Wight, Southampton seemed to Keats an exemplar of the habitual and mundane, and disappointed him by meeting his expectations so unerringly.

Visual artists, too, have at times found in Southampton a challenging subject. J. M. W. Turner did a series of sketches in 1827 while watching the Cowes Regatta, but these failed to produce a finished artwork. James McNeill Whistler did paint Southampton. His Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Southampton Water (1872) was one of the first of his ekphrastic pictures, reconceiving as it does the view of the harbour as a musical form. Yet the ordering of his title may also suggest that, to Whistler, the specifics of place are subordinate to considerations of style and tint—and the artist has been taken at his word by the painting’s holding institution, the Art Institute Chicago, which interprets the image thus: ‘Although the work is based on his experience of the location, the specifics of place are inconsequential.’

Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Southampton Water James McNeill Whistler, 1872

Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Southampton Water James McNeill Whistler, 1872

Recently, a number of critics have emphasised the sea’s invisibility as instrumental to its function in modernity. John Urry, for instance, writes that oceans ‘assemble as secret what would otherwise be onshore and visible’, while according to Allan Sekula, ‘The metropolitan gaze no longer falls upon the waterfront, and a cognitive blankness follows.’ These are theoretical comments, which may seem not to have concrete effects, but the issue is practical too since some of the major crises associated with the sea take place, not only in the context of, but as a function of, the sea not being seen.

Southampton offers a good vantage point from which to attend to these concerns. Since the late nineteenth century, it has become still more difficult to say to what degree the specifics of Southampton as marine inspiration might have mattered to Whistler, Keats, or any of the other writers and artists mentioned here. This is because between 1892 (when the Royal Pier opened) and 1934 (when the New Docks opened) the Southampton seaside that Whistler saw, and that Keats and Austen would also have recognized, was gradually transformed into industrial space through a programme of land reclamation that completely erased the place as it had existed prior.

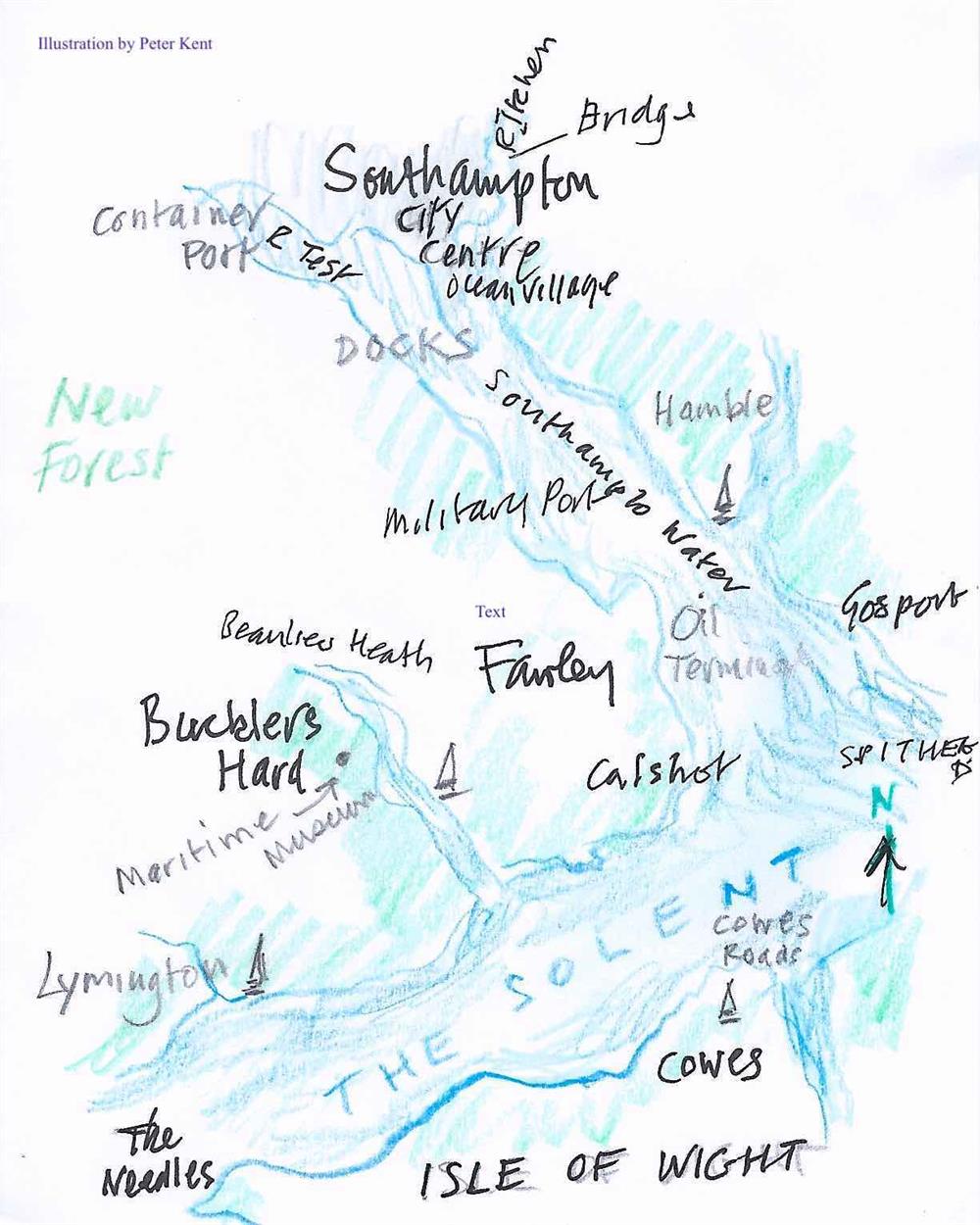

Today, Southampton provides a useful model of the sea’s invisibility in part because Southampton is a place that routinely escapes notice. It cannot conform to picturesque ideals of seaside towns: Southampton was bombed heavily during the Second World War, and hurriedly rebuilt. It is a major cruise terminal, but not a destination for tourists. You would never know, but it is the primary point of entry for cars and trucks shipped from overseas. Across Southampton Water, the Fawley refinery supplies 20 per cent of the United Kingdom’s oil—much of it invisibly, by direct pipeline. The docks are inaccessible to the public, and no bathing is possible in the city itself. But if the sea in Southampton is now more or less practically invisible, its invisibility is part of a longer history of British travel to the seaside, where anticipation and reality, the health-giving and the overwhelming, the particular and the general, have often met to obscure the specific qualities of even the most significant of seaside places.

Dr Matt Kerr is a Lecturer in British Literature from 1837 to 1939 at the University of Southampton.

Matt’s research and teaching centre on Victorian literature and culture. His work spans both well-known figures— Dickens, Mill, Ruskin—and neglected ones, such as Captain Marryat. His articles have appeared in Essays in Criticism, Review of English Studies, and Dickens Studies Annual, among other places.

Matt co-edited Coastal Cultures of the Long Nineteenth Century, published in August 2018 by Edinburgh University Press.

Please log in to create your comment