12 PORTS: STROMNESS – MADE OF STORIES

08 July 2019

The fifth in a series of articles following sailor Jonathan Winter on a voyage around 12 ports of Britain and Ireland. In this piece, Nick Isbister finds Stromness is made of stories.

Stromness, from the Norse Straumsnes, means the ‘headland protruding into the tidal stream’. The Vikings called it Hamnavoe: ‘peaceful’ or ‘safe harbour’. It is the second-most populous town in ‘Orkneyjar’, (Old Norse for ‘Seal Islands’).

Source: SURF: Scotland’s Regeneration Forum

Poet and novelist, George MacKay Brown (GMB) lived there all his life and in his poem, ‘Hamnavoe’ sees it as the safe haven for ‘boats [that] drove furrows homeward, like ploughmen, in blizzards of gulls’.

GMB went away to Edinburgh for his education, but returned to Stromness to live, and love and write. He is buried there too. Composer, Sir Peter Maxwell Davis, formerly Master of the Queen's music chose to live there, or thereabouts. It seems that Orkney holds a strange magnetism for those who encounter its storm-ridden, windswept, desolate charms. It finds its way into people’s personal stories.

My Story

At the age of eleven I learned that there was a set of Islands just North of Scotland where there were many people with my name. Then I learnt that 5000 years ago at a place called Isbister there was a unique chambered tomb where humans were buried with the bones of 14 white-tailed sea eagles, now known as the ‘Tomb of the Eagles’ – a chambered tomb on top of a dramatic cliff:

Source: Tomb of the Eagles

I was hooked. I was ‘connected’ to a past; I had a distinctive heritage; I had a place I could think of as ‘where I’m from’. I may not be living there, but my identity had roots, my name took me on the genetic path that is the equivalent of the stone-path constructed as a timeline from the visitor centre at Skara Brae through the sand-dunes all the way to the remarkable stone houses dating back to 3200 BC. That’s a long, long path. The first man on the moon, the Declaration of Independence, 1066, the fall of Rome, the birth of Christ, the great wall of China, the pyramids, and still the path goes on. Of course, it is all a story I tell myself, but that’s the point: we are our stories.

“The universe is made of stories, not of atoms.” – Muriel Rukeyser

Far from being ‘off-the-beaten-track’ Orkney was the beaten track – 5000 years ago – and even in the 20th Century they became central once again. Whole books have been written about the significance of Orkney during the two World Wars. A key naval centre, 100 years ago exactly the German navy scuttled its fleet in Scapa Flow.

The archeologist in charge of the excavations at the Ness of Brodgar puts it like this:

“We need to turn the map of Britain upside down when we consider the Neolithic and shrug off our south-centric attitudes, London may be the cultural hub of Britain today, but 5,000 years ago, Orkney was the centre for innovation for the British isles. Ideas spread from this place. The first grooved pottery, which is so distinctive of the era, was made here, for example, and the first henges – stone rings with ditches round them – were erected on Orkney. Then the ideas spread to the rest of the Neolithic Britain. This was the font for new thinking at the time.” – Nick Card of the Orkney Research Centre for Archaeology.1Neolithic discovery: why Orkney is the centre of ancient Britain, The Guardian, 6th October 2012

Seeing the world from a different perspective

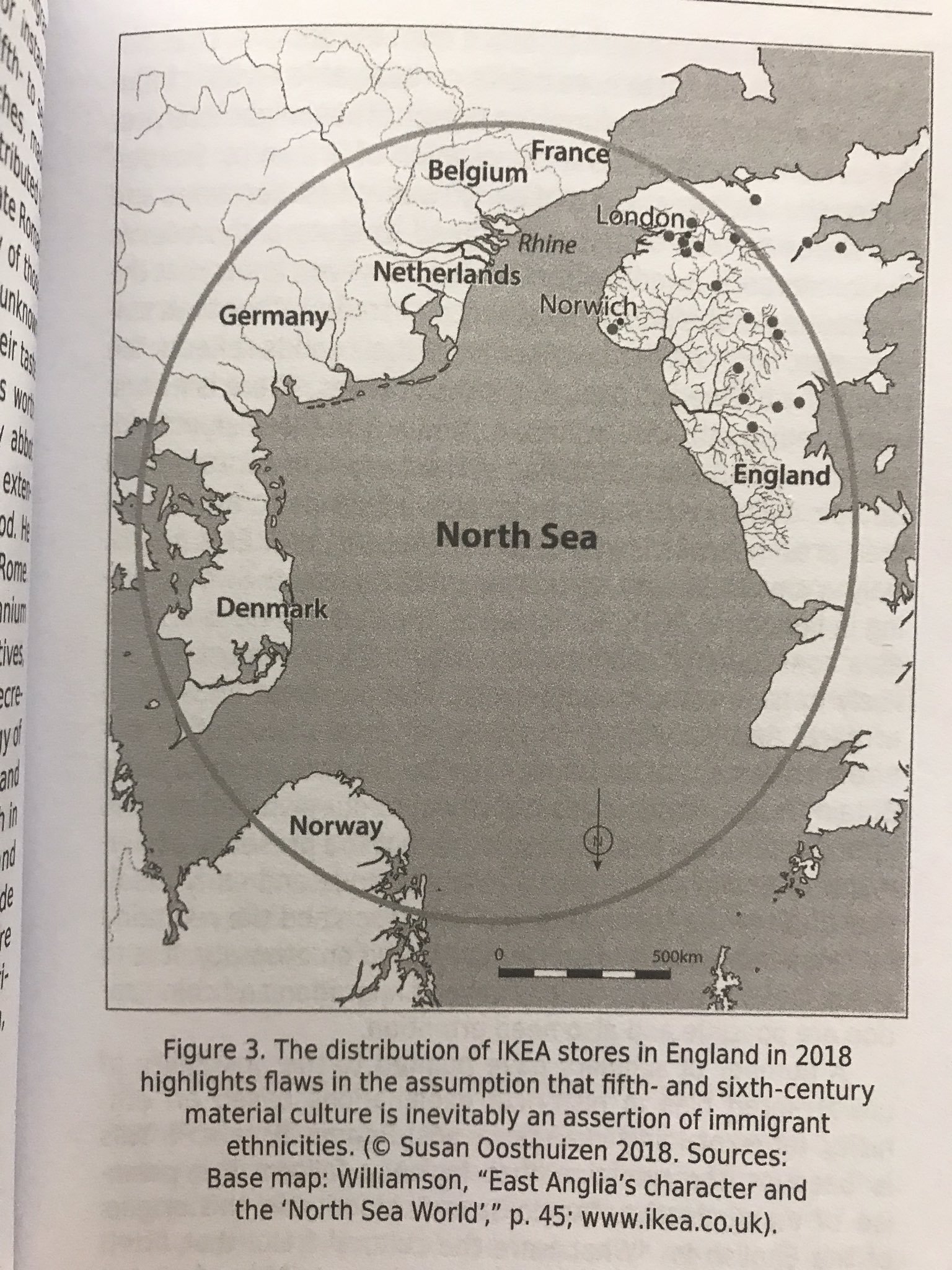

Nick Card is right when it comes to thinking about ‘the world’ as it was in Neolithic times. Those of us in the geographic south need to lose our London-centric, Southern bias and see the world differently. This is reinforced – in relation to a later period – by Archeologist Susan Oosthuizen in her book ‘The Emergence of the English’, in which she puts forward a radical view of how post-Roman Britain became Anglo-Saxon England. She argues that the traditional view that it all happened through the three ‘A’s – Abandonment, Assimilation or Annihilation – is wrong, rather it happened much less dramatically and demonstrates much more continuity than the traditional paradigm implies. As she says, the history of this period is a history of how people ‘expressed collective identities drawn from the landscapes they occupied, and among whom continuity may have been as commonplace as transformation’. Her book reinforces this with a simple but clever map of the region:

The map makes the point brilliantly. Little wonder then that, during the very period she is talking about Orkney was a vital stopover as the Vikings came and saw and settled.

Triumphs of the human spirit

Source: Kieran Baxter

What an astonishing group of people committed themselves to create such monumental works as the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness. When dedicated as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1998 the commendation said:

“The monuments at the heart of Neolithic Orkney and Skara Brae proclaim the triumphs of the human spirit in early ages and isolated places. They were approximately contemporary with the mastabas of the archaic period of Egypt (first and second dynasties), the brick temples of Sumeria, and the first cities of the Harappa culture in India, and a century or two earlier than the Golden Age of China. Unusually fine for their early date...these sites stand as a visible symbol of the achievements of early peoples away from the traditional centres of civilisation...The Ring of Brodgar is the finest known truly circular late Neolithic or early Bronze Age stone ring.”2Statement of Significance, Historic Environment Scotland

The Ness of Brodgar, the Stones of Stenness, The Ring of Brodgar, all constructed before the pyramids. A number of groups of people committed themselves to work on these extraordinary endeavours – the archaeological evidence suggests that different parts of the henge were developed by different groups. Look what can be achieved when people commit to a common purpose, and vest something of their identity in something beyond mere subsistence. When people decide to assert their identity, whether to themselves or to ‘others’ or, perhaps most pertinently to this enduring monument, to something or someone or some many others (ancestors) beyond the here and now, it sends a powerful message.

Vandals?

‘Vandals deface historic monument’. On the 11th April just a few days before yacht Nova set out around these islands, the BBC ran this headline: ‘Police are investigating vandalism at Orkney's Ring of Brodgar.’ The story continues:

“Built 5,000 years ago, the Neolithic ceremonial site near Stenness is the third largest stone circle in the British Isles. Graffiti was scratched into one of the ring's 27 standing stones sometime between Friday afternoon and Sunday morning. Police Scotland described the stones as ‘priceless artefacts’ and the vandalism as a ‘mindless act’.”3Graffiti scrawled on Ring of Brodgar standing stone in Orkney, BBC News Website, 11th April 2019

Source: Graffiti scrawled on Ring of Brodgar standing stone in Orkney, BBC News Website, 11th April 2019

‘Vandalism’ – the activity of ‘vandals’. Mindless, thoughtless Vandals. Maybe the Goths, and the Visigoths and the Vandals were more destructive than other invaders of ancient times, they certainly inspired John Dryden to write, ‘Till Goths, and Vandals, a rude Northern race, Did all the matchless Monuments deface’ (‘To Sir Godfrey Kneller’, 1694).

The historic monuments of Orkney have repeatedly been the objects of such defacing. The Neolithic Chambered Tomb of Maeshowe houses one of the largest collections of runes outside Norway. According to the Orkneyinga Saga, a medieval ‘history’ of the Earls of Orkney, the runes were written by a group of Viking raiders who took refuge in the tomb from a storm:

Source: JN Isbister 2001

The Maeshowe’s runes are manifestly graffiti – ‘Ingebjork the fair widow – many a woman has walked stooping in here a very showy person’ signed by Erlingr; ‘Thorni f*cked. Helgi carved’ (most guidebooks substitute a more acceptable translation to this); ‘Ofram the son of Sigurd carved these runes’; ‘Haermund Hardaxe carved these runes’.

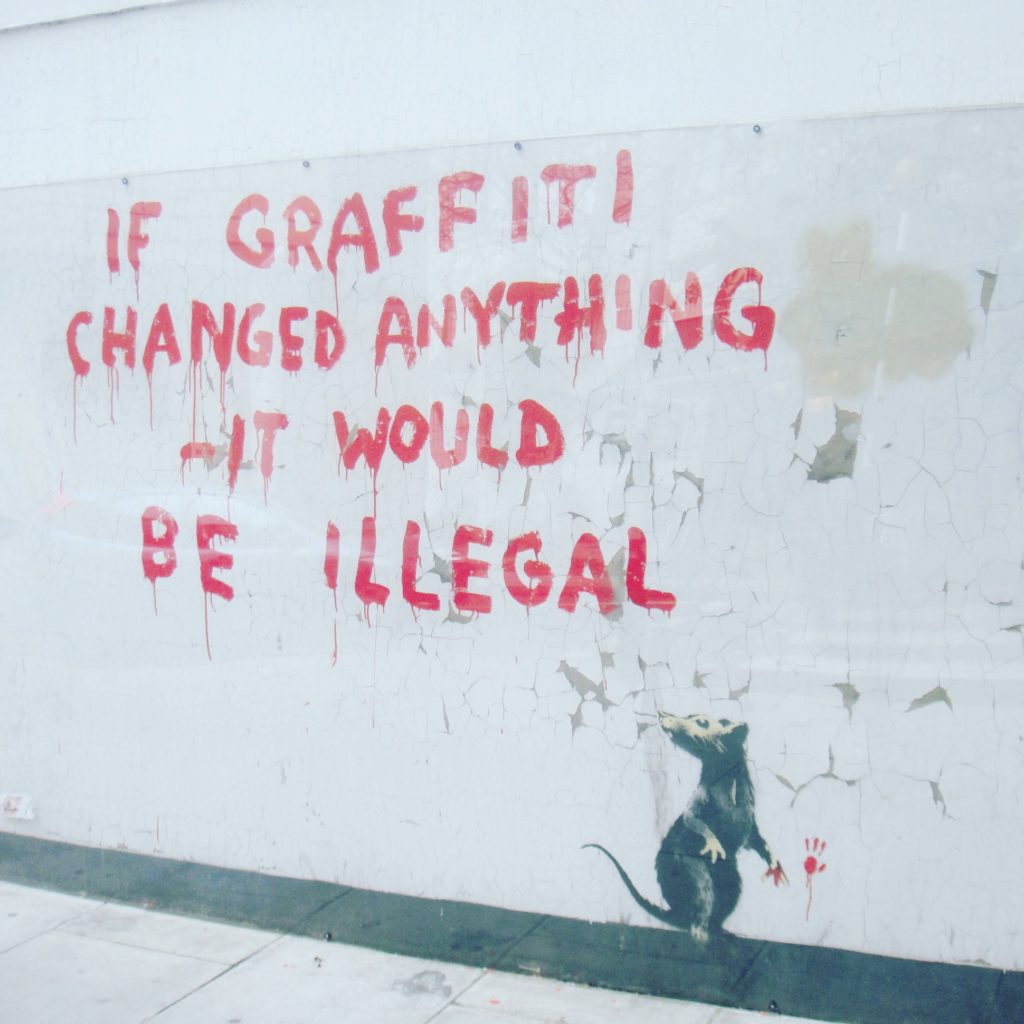

Are these mindless acts of vandalism, or are they assertions of individual identity? We treasure the Viking graffiti now; maybe we will never treasure the crude scrawls that were added to the stones at Bodgar. To suggest that they might not be mindless is not to endorse or condone them. But they can be framed in other ways. Certainly, Banksy would:

Source: Banksy. World Graffiti Artist. His technique, career and work

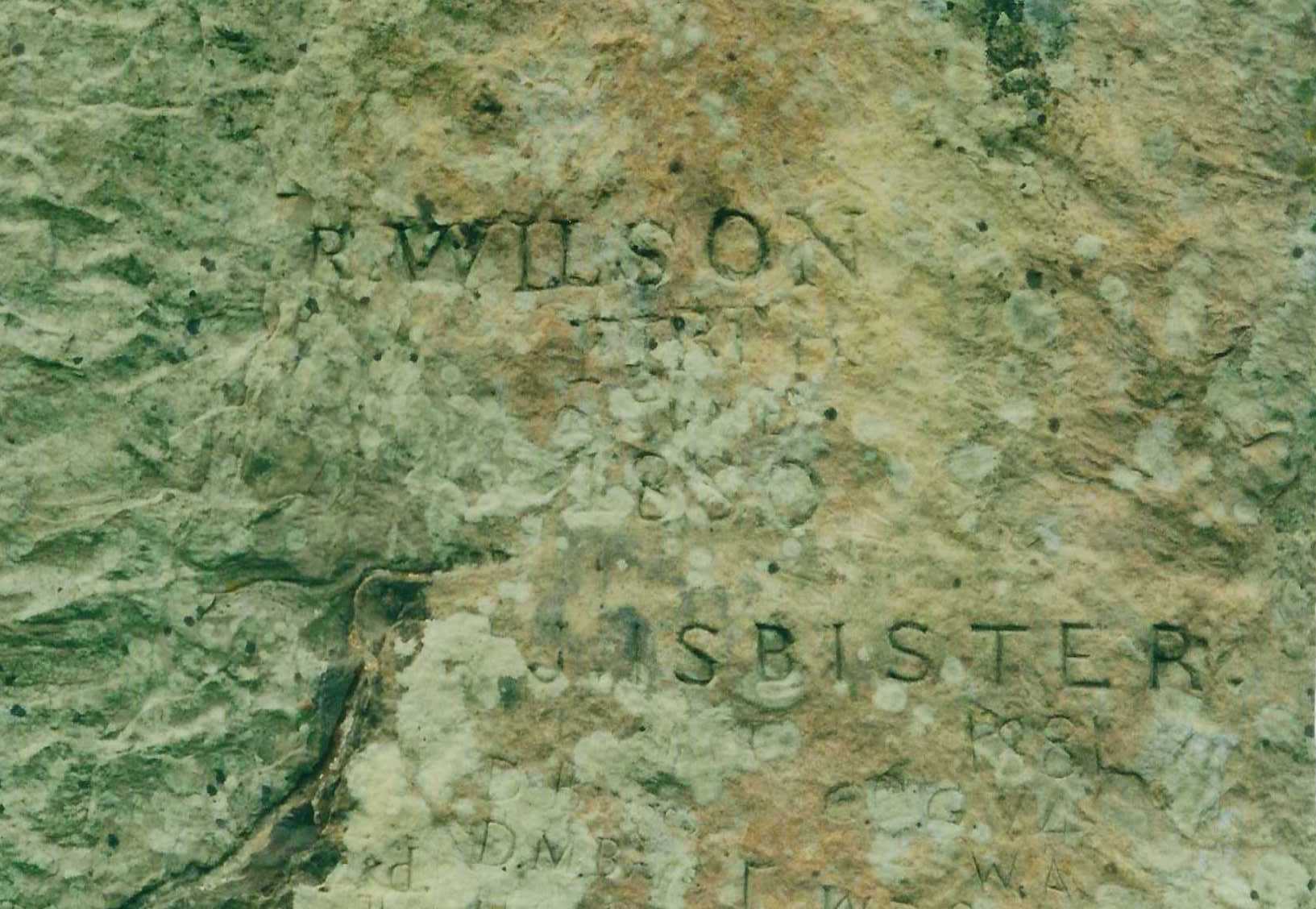

Interestingly, my visit to the Ring of Brodgar in 2001 left a profound impression on me, not least because in this astonishing assertion of collective identity, hidden away on one of the stones was some ancient graffiti – the name J Isbister, my name with the date 1881:

Source: JN Isbister 2001

Whilst I am a great fan of Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander TV Series, I’m unconvinced that I travelled back in time to carve my name as a ‘mindless act of vandalism’. But I do feel an astonishing sense of continuity, and indeed meaning for me in this simple piece of graffiti. George MacKay Brown concludes his autobiography with these words:

“... stories from under the horizon ought always to be welcome – and so they have been, in Orkney, for centuries: but they are never utterly new. There are mysterious marks on the stone circle of Brodgar in Orkney, and on the stones of Skarabrae village from 5000 years ago. We will never know what they mean. I am making marks with a pen on paper, that will have no meaning 5,000 years from now. A mystery abides. We move from silence into silence, and there is a brief stir between every person’s attempt to make meaning of life and time. Death is certain; it may be the dust of good men and women lies more richly in the earth than that of the unjust; between the silences they may be touched, however briefly, with the music of the spheres.”4For the Islands I Sing: An Autobiography, George Mackay Brown

‘We move from silence into silence, and there is a brief stir between every person’s attempt to make meaning of life and time’. Some build monuments, some carve their names on those monuments, some ‘make marks with a pen on paper’ all in the attempt to make meaning of their lives. Our identities hold and collate that meaning. And maybe as TS Elliot said, ‘home is where we start with’, but then he concluded ‘Old stones that cannot be deciphered’ (both quotes are from ‘East Coker’ – no. 2 of 'Four Quartets'), or, maybe they can be? GMB’s gravestone bears an inscription from the last two lines of his 1996 poem, ‘A work for poets’:

Carve the runes

Then be content with silence.

Our silences may be touched with the music of the spheres or they may be lifted by Sir Peter Maxwell Davis’s wonderful Farewell to Stromness.

Nick Isbister (JN Isbister) is an executive coach, and the author (with his wife, Jude Elliman) of The Story So Far: Introduction to Transformational Narrative Coaching, The Isbister Press

Please log in to create your comment