WHAT IS THE UK SINGLE MARKET?

20 August 2019

What Brexit will mean for the UK’s trading relationships with the EU and the rest of the world remains an open question. But there is one thing of which we can be certain: whatever happens, free trade within the United Kingdom will continue as before.

It’s such a fact of life that it’s easy to forget: goods and services flowing between the four nations of the UK do so in a perfectly free market. There are no tariffs, and very few non-tariff barriers.

And the reason this will continue as before, whatever happens with Brexit, is the existence of the UK single market.

Establishing a UK single market and customs union was integral to the 1707 Act of Union. The language may be archaic, but the meaning of these clauses is unambiguous – freedom of movement, a single market, a customs union, a single currency – and they remain on the statute book today:

That all the Subjects of the United Kingdom of Great Britain shall from and after the Union have full Freedom and Intercourse of Trade and Navigation... [Section IV]1http://www.legislation.gov.uk/aosp/1707/7/section/IV

That all parts of the United Kingdom for ever from and after the Union shall have the same Allowances Encouragements and Drawbacks and be under the same Prohibitions Restrictions and Regulations of Trade and lyable to the same Customs and Duties on Import and Export... [Section VI]2https://www.legislation.gov.uk/aosp/1707/7/section/VI

That from and after the Union the Coin shall be of the same standard and value throughout the United Kingdom as now in England. [Section XVI]3https://www.legislation.gov.uk/aosp/1707/7/section/XVI

That the Laws concerning Regulation of Trade, Customs and such Excises to which Scotland is by virtue of this Treaty to be lyable be the same in Scotland from and after the Union as in England... [Section XVIII]4https://www.legislation.gov.uk/aosp/1707/7/section/XVIII

The absorption of the UK single market into the EEC, and later the EU single market, has meant that since 1973 many of the rules governing the UK single market have been made at the EEC/EU level.

Brexit means these EU competencies will have to be repatriated to the UK, and there has been a lively debate around whether the powers should go to Westminster or to the devolved nations. The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 sends the majority of them to Westminster, for the straightforward reason that these powers are essential to the maintenance of the UK single market.

The characterisation of this as a Westminster “power grab” is difficult to justify: if one accepts that the powers have been held at the EU level to ensure the integrity of the EU single market, it should be uncontroversial that maintaining the integrity of the UK single market depends on them being held at the UK level post Brexit. This is one of the reasons why the UK single market has become a surprisingly contentious topic – its existence undermines the “power grab” narrative.

The 1707 Act of Union explicitly established the UK single market (and the customs and currency unions), but there are plenty of contemporary examples demonstrating that the UK single market is still with us, and is quite distinct from the EU single market.

One of the four freedoms underpinning the EU single market is the free movement of people. But that freedom of movement is really the free movement of workers – it is employment contingent, with the only exception being people who are wealthy enough “not to become a burden on the host Member State’s social assistance system”.5http://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/41/free-movement-of-workers

Within the UK there is no such contingency: the greater level of integration within the UK single market means that movement of people is completely free. Of course the UK also has enhanced freedom of movement with Ireland, by virtue of the Common Travel Area – but this just reinforces the fact that the UK single market exists as a distinct entity within the broader EU single market.

At the time of writing it is still unclear what form Brexit will take, or if indeed it will happen at all. But whatever happens, trade frictions will be central to understanding the consequences. Any form of Brexit – except the softest possible exit of staying inside the EU single market and customs union – will mean trade frictions between the UK and the EU.

When it comes to the vexed question of Scotland’s constitutional future, this really matters. If Scotland is forced to choose between being in either the UK single market or the EU single market, the relative importance of those markets to Scotland’s economy becomes a critical consideration.

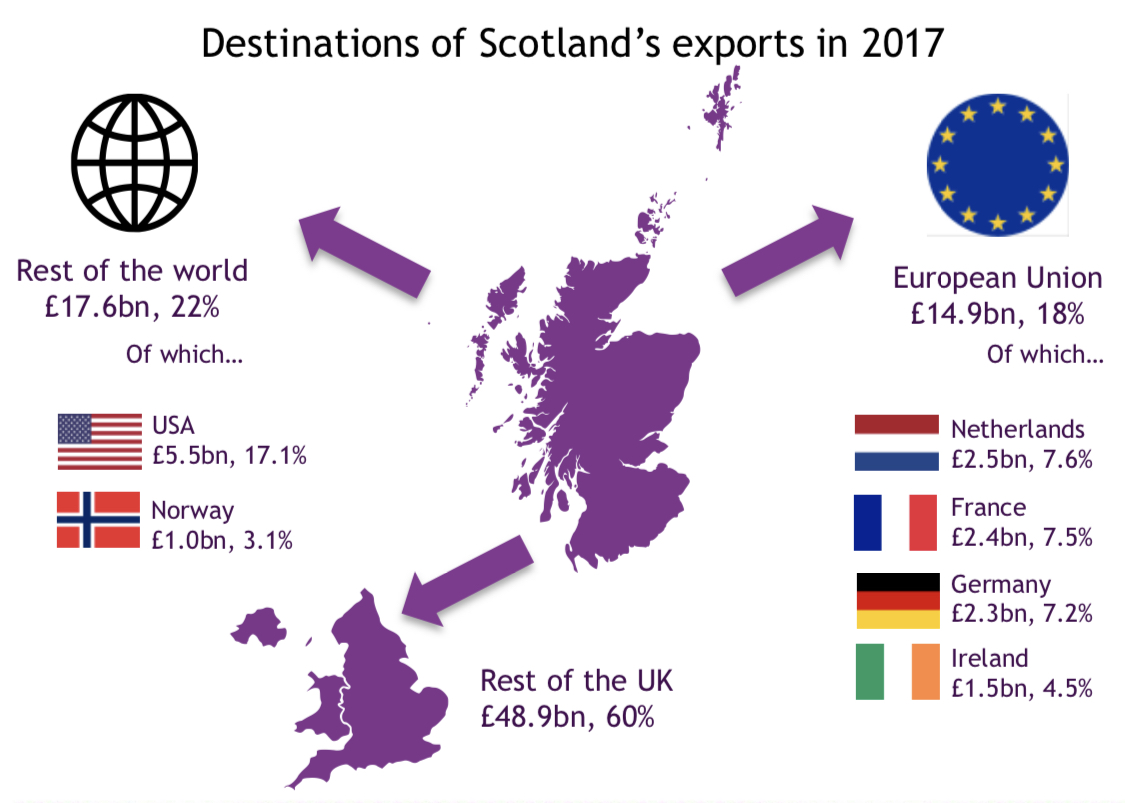

The UK single market is overwhelmingly Scotland’s most important export market. In fact, Scottish exports to the rest of the UK are worth more than three times as much as exports to the EU:6https://www2.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Economy/Exports/ESSPublication

To avoid any confusion about what these figures represent, this explanatory note from the statistical release is very important:

In calculating these figures we look at the final destination of the exports and ensure exports originating in Scotland are allocated to Scotland. For example, a sale by a Scottish company to a customer in France which is shipped via a port in England, would still be classified as a Scottish export to France, rather than a Scottish export to the rest of the UK.7https://www2.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Economy/Exports/ESSPublication

Data on imports is not quite as good, but we do know that in 2017 Scotland imported goods and services worth £58.4bn from the rest of the UK, which represented 66% of total imports.8GDP Quarterly National Accounts, Scotland So the relative importance to Scotland of the rest of the UK is even greater for imports than for exports.

If Brexit results in trade friction between the EU and the UK, then an independent Scotland within the EU would face those same trade frictions when trading with the rest of the UK. This does not mean that trade would cease – any more than those arguing against Brexit are suggesting that trade with the EU will cease – but it would become more difficult.

Unless they happen to be employed in an exporting industry, people can sometimes find the problems of exporters to be a remote and fairly abstract concern. But imports are a different matter: everybody buys stuff, and in Scotland, a very great deal of what people buy comes from the rest of the UK.

In 2017, final consumption by households in Scotland was £97.4bn9GDP Quarterly National Accounts, Scotland, which puts £58.4bn of imports from the rest of the UK starkly into perspective. Some imports represent investment by businesses and government expenditure, so it does not make sense to simply divide one number by the other, but it’s fair to say that roughly one in every two pounds spent by Scottish households is spent on buying imports from the rest of the UK. Trade friction (increased prices and/or reduced availability) between an independent Scotland and the rest of the UK would impact on ordinary people in a very real and tangible way.

Of course these trade statistics are about the past. Advocates for Scottish independence might well argue that the EU, as the much bigger market, represents the greater future opportunity. With the prospects for the UK economy decidedly uncertain post-Brexit, choosing the EU single market in preference to the UK single market is superficially appealing.

But it bears repeating: the UK single market is more than three times as important to Scotland. This is not surprising given the history of the UK single market, the existence of what we might call the Sterling Zone, and the practical realities of geography and language. Even if the currency were to change (the SNP policy seems to be one of creative ambiguity on this question) the facts of geography and language will not change if Scotland leaves the United Kingdom.

The concept of ‘gravity’ exists in international trade: it describes the inverse relationship between bilateral trade flows and the distance between two countries. Just like regular gravity, it’s a very difficult thing to escape.

Paradoxically, independence would actually increase the importance of the UK single market to Scotland. This is because the SNP’s own blueprint for independence – the Sustainable Growth Commission report – anticipates that Scottish banks will redomicile to London, meaning that an independent Scotland would rely on importing virtually all financial services from the UK. If Scotland was inside the EU and there was no deal between the UK and the EU, that arrangement would be fraught with difficulty.

Independence supporters are sensitive about the comparison, but arguing that Scotland must break from a dysfunctional UK because of the vital importance of the EU single market echoes Brexit supporters who argued the UK must unshackle itself from a dysfunctional EU in order to forge closer ties with its larger market, the rest of the world.

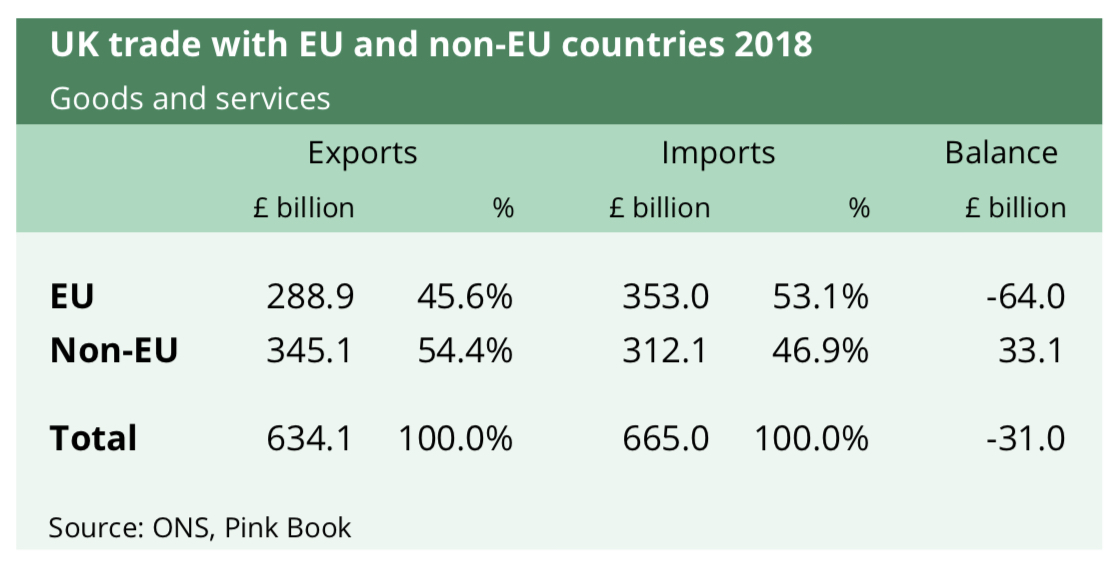

But there is an important difference. The data is clear that the UK is relatively far more important to Scotland than the EU is to the UK – the UK does actually export more to the rest of the world than it does to the EU:10House of Commons Library Briefing Paper: Statistics on UK-EU trade

Those arguing against Brexit but in favour of Scottish independence are faced with a conundrum: if the “Brexit for free-trade with the world” argument is wrong, the “Scottish Independence for free-trade with the EU” argument must be many times more wrong.

The debate about Scotland’s constitutional future will always involve passionate arguments, but all sides should be able to agree that the UK single market exists. And that if Brexit creates trade frictions between the UK and the EU, choosing to leave the UK single market in favour of the EU would be choosing to damage Scotland’s most important trading relationship.

Please log in to create your comment