SCOTLAND’S NEXT FINANCIAL CRISIS?

08 February 2021

With Scotland's ruling party planning a second referendum followed by a swift exit from the UK, Scots could find themselves living under a 'sterlingisation' currency system within the next few years. The implications for the country would be profound. By John Ferry.

While governments across the world have been preoccupied with fighting the Covid-19 pandemic, the Scottish National Party (SNP) administration in Edinburgh has also been busy pursuing its aim of taking Scotland out of the UK.

In September, the Scottish Government, led by First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, set out its legislative programme for the next parliamentary year and announced it would publish a draft bill outlining the proposed terms for a second independence referendum. More recently, it was revealed that the Nationalist's constitution spokeserson Mike Russell had held a meeting with the Australian High Commissioner in November, during which he stated his "hope" that a second referendum would be held by the end of 2021, following an expected SNP win at the Holyrood elections in May. Then in January Nicola Sturgeon announced her intention to hold a referendum after the May election – with or without UK government approval.

Many observers scoff at the idea of another independence referendum while the UK continues to struggle with the impact of Covid-19, but the possibility of one taking place in the not-too-distant future is real. Powers over the UK's constitution may sit with Westminster, but polling in 2020 demonstrated a sustained small majority for secession for the first time, while the SNP continues to ride high in the polls.

That begs the question of how Scotland will fare economically if it exits the UK in the coming years, and in particular the thorny issue of its currency regime once formally outside the sterling currency zone. On this, the SNP has a plan, outlined in a lengthy report published in May 2018 by its Sustainable Growth Commission – a group set up by the party to provide a credible economic blueprint for separation.

The intention is to maintain sterling as the currency used within Scotland but outside of a formal monetary union with the remaining UK – the SNP's assumption that the remaining UK would agree to a monetary union proved a major achilles heel for the pro-separation movement in the run up to the 2014 independence referendum once the idea was rejected by Westminster. An independent Scotland will, therefore, operate under a 'sterlingised' currency system.

Specifically, the plan is to use the British pound unofficially while putting in place an independently managed Scottish financial system with a newly established Scottish Central Bank (SCB) at its core. The SCB will provide liquidity support to Scottish retail banks and be lender of last resort, while also providing a payments system for clearing transactions in Scotland. The SCB will be banker to the Scottish Government and will have a subsidiary, the Scottish Financial Authority (SFA), that will mirror the oversight and other activities of the UK's Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA). The SCB will also be responsible for a new Scottish version of the UK's statutory deposit insurance scheme.

Using another country's currency unofficially – often referred to as 'dollarisation', given the dominance of the US dollar – is not uncommon. Panama for example has used the US dollar unofficially since 1904, while a number of emerging market countries have experimented with dollarisation in recent decades in an effort to import credibility to their financial systems and control inflation. But applying such a model to the break-away part of an advanced economy would be a first.

Risky experiment

"I think it would be a hugely risky experiment for Scotland," says Dame DeAnne Julius, one of the founding members of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee and a former Chief Economist at British Airways and Shell. "The evidence one could look to for this kind of arrangement are places that are quite different and at a different development level – places like Argentina – and it's impossible, I think, to find any place that is a success story undertaking this route of political independence using a currency issued by another country."

"I think Scotland would have to undergo a profound change and would probably have to make some difficult economic adjustments," says Harvard University economist Professor Jeffrey Frankel, who served on the US President's Council of Economic Advisers during the Clinton administration and has published extensively on exchange rate regimes.

Sterlingisation has important implications for two distinct, but related, issues: the stability of the banking system, and the ability of the economy to absorb macroeconomic imbalances.

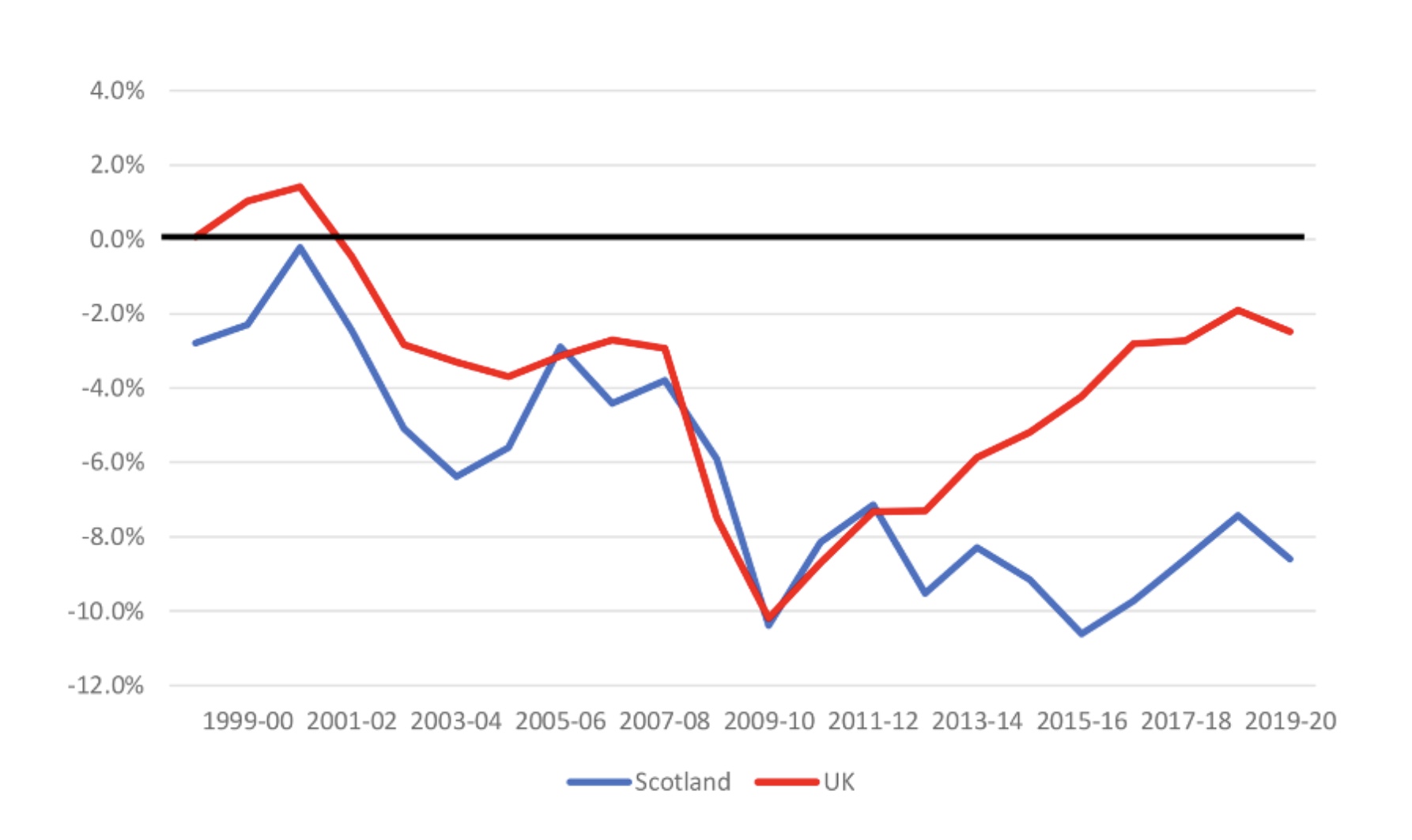

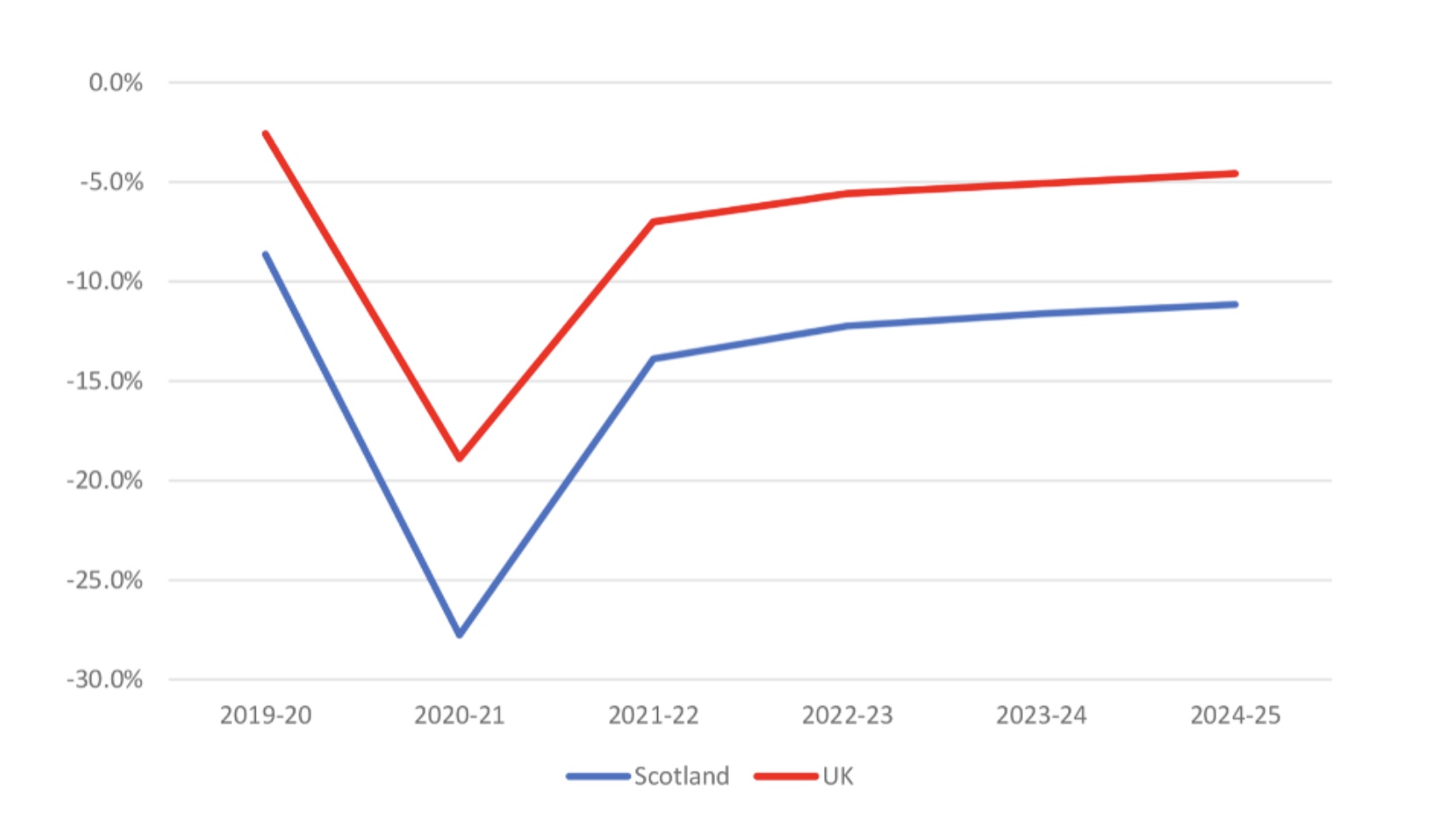

On the macroeconomic position, the new state would start with a large fiscal deficit and a large current account deficit (the current account is a key component of the balance of payments, which is a measure of all cross-border transactions over a particular time period). According to Scottish Government data, Scotland's implicit budget deficit for 2019/20 was 8.6% of Scottish GDP, which meant the country spent £15 billion more than it raised in taxes, while Scotland's trade figures suggest persistently large current account deficits. The current account deficit for 2017, the latest year for which firm data exists, was around 7.6% of GDP, and it was 10% of GDP in 2016.1The current account balance is obtained by summing the net trade balance and the net primary income balance. The data at both links is compiled by Scottish Government statisticians. Taking into account current Covid-19 spending pushes the implicit budget deficit out considerably. The UK's Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates Scotland's 2020/21 budget deficit at 26-28% of GDP, and projects double-digit Scottish deficits through to 2025 (see graphs at the foot of this piece).

With Scotland inside the United Kingdom, these imbalances are manageable. Fiscal transfers from the UK Government mean that Scotland can run persistent deficits without relying on borrowing from capital markets. And the Bank of England ensures that Scottish banks have the liquidity necessary to keep the economy moving, and that households and businesses can access credit and rely on deposit insurance on the same terms in Scotland as anywhere else in the UK. But with independence the fiscal deficit would have to be plugged by borrowing on capital markets, and Scottish banks could no longer rely on the Bank of England for liquidity – a significant issue when Scotland’s current account balance means there would be a substantial outflow of sterling from the Scottish banking system.

"Scotland has no credit history and would have an unstable macroeconomic situation, so debt issued by its central bank would be high risk for investors, who would demand a high interest rate to hold it," says Julius. "Those higher interest costs would be a huge additional burden to a Scottish government that ran a budget deficit needing to be financed by debt."

"Looking at the massive Scottish fiscal and current account deficits, my advice to the new prime minister, should the country split off, would be to address these structural challenges or develop good links with the IMF [International Monetary Fund], because she or he might well need their assistance in the future," says Professor Cédric Tille, member of the Bank Council of the Swiss National Bank and Head of the Bilateral Assistance and Capacity Building for Central Banks Programme at the Graduate Institute Geneva. "This to me is a big problem for Scotland. It's really reliant on external funding."

There are ways to address the macroeconomic imbalances. Recessions can turn trade deficits into surpluses, while large tax rises or cuts in government spending, or a combination of both, would cut the fiscal deficit. The Sustainable Growth Commission advocates bringing Scotland's budget deficit down gradually over 10 years via spending restraints, but it seems clear that large-scale government spending cuts and/or tax rises would be required immediately.

"Essentially, if you're going to be effectively using someone else's currency then you've got to be extremely fiscally prudent," says Charles Goodhart, Emeritus Professor of Banking and Finance at the London School of Economics and former Chief Adviser at the Bank of England.

An unstable banking system

Concerns surrounding the commercial banking system stem from the ability of the new SCB to be a credible lender of last resort. The Sustainable Growth Commission makes the case that financial support would only be provided to ring-fenced retail entities operating in Scotland, with those entities regulated to "ensure that adequate collateral is available to match retail deposits in such banks". It also assumes that the very large Scottish banks, Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and Lloyds Banking Group (which Bank of Scotland is part of), would likely move their domicile to the remaining UK so as to maintain support from the Bank of England. The scale of liquidity support the SCB would be expected to provide in a crisis would therefore be "manageable", says the Commission.

Julius questions this assumption. "I don't see how the Scottish Central Bank could be the lender of last resort. It cannot create sterling, and so it could not fulfil that function unless Scotland has accumulated a very large stock of sterling that the central bank or the government had access to," she says.

Goodhart points to the fact that the deposits commercial banks would hold at the SCB would not be the equivalent of reserve accounts at the Bank of England. "Commercial bank reserve deposits are just as much money as currency, notes and coins, so how do you provide liquidity support other than by creating reserve deposits, which is the equivalent of creating money?" he says.

Frankel points out that the probability of the country experiencing a run on its banks would be higher under a sterlingised system because investors and depositors would take into account the fact that the central bank is constrained in its liquidity support, which itself would lower confidence in a crisis, and he contrasts the proposed Scottish system with the CFA franc zone in Africa. "What's allowed the CFA franc during most of its history to maintain its stability is that the Banque De France was willing to smooth things over and be the lender of last resort," he says.

Even if the SCB is, on paper, a lender of last resort, the reality on the ground for commercial banks would be a vastly different operating environment to what they had before. Alan Sutherland, Professor of Economics at St Andrews University, says banks operating in Scotland would "feel themselves to be exposed to different types of risk in Scotland compared to the remaining UK, and they may well themselves choose to have entirely separate subsidiaries operating in Scotland".

Sutherland continues: "To me, the question of currency is actually multi-layered. It's not just, do we have a means of payment and do we have liquidity. That's one element of currency. Arguably, a much more important element of currency and the banking system is what the borrowing and lending terms available to customers are – what level of risk judgements lenders make when granting credit. Some borrowers will just not get mortgages anymore, some businesses will not get loans, rates of interest will be much higher. And some products will simply not be offered."

If banks – namely the two big ones, Lloyds Banking Group and RBS – opt to have separate subsidiaries operating in Scotland for group risk management purposes, then those banks' Scottish operations would reflect the risks their businesses are taking. Says Goodhart: "No doubt head office [of Lloyds and RBS] in London would want its Scottish subsidiary to be viable, but I doubt whether it would provide them with more than the minimum of equity and liquid assets necessary to meet financial regulations. But my guess is that the balance sheet would have to involve sizeable intra-bank loans from head office for the Scottish subsidiary. I would expect that such loans would now carry a higher interest rate because of the greater default risk in Scotland."

"What could happen in a crisis is that the UK banks – or policy makers – could focus on their domestic activities, and not consider so much their foreign activities, including in Scotland," adds Professor Tille.

There is, therefore, no way to achieve separation without fundamentally changing Scotland's financial system in a way that could have a dramatic impact on households and businesses. The recognition of that alone, following a vote to secede, would likely have profound implications for Scotland. "I would think within a very short time [after secession] we would start to see financial problems," says Sutherland. "And in advance of that we would start to see a movement of savings and capital out of Scotland."

Capital flight, higher interest rates, households and businesses finding it more difficult to borrow – not exactly the foundations of a stable new state. Yet the ever-popular SNP insists separation will happen, and happen soon. The groundwork for Scotland's next financial crisis might be being laid now.

Figure 1: Scottish and UK budget deficits, % of GDP, 1998-99 to 2019-20

Notes: Positive figures are surpluses, negative figures deficits. Deficit measure is the Net Fiscal Balance including a geographic share of North Sea revenues for Scotland.

Source: Institute for Fiscal Studies, Scotland’s implicit budget deficit could be around 26-28% of GDP in 2020-21, 26 August 2020, using source data from Government Expenditure Revenue Scotland 2019-20.

Figure 2: Projections of Scottish and UK budget deficits, % of GDP, 2019-20 to 2024-25

Notes: Positive figures are surpluses, negative figures deficits. Deficit measure is the Net Fiscal Balance including a geographic share of North Sea revenues for Scotland.

Notes: Positive figures are surpluses, negative figures deficits. Deficit measure is the Net Fiscal Balance including a geographic share of North Sea revenues for Scotland.

Source: Institute for Fiscal Studies, Scotland’s implicit budget deficit could be around 26-28% of GDP in 2020-21, 26 August 2020, using source data from Government Expenditure Revenue Scotland 2019-20, and the Office for Budget Responsibility’s Fiscal Sustainability Report and Policy Monitoring Database.

An abridged version of this report was published by the Spectator, on 7th February 2021.

Please log in to create your comment