WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT SCOTLAND

26 June 2022

In a piece first published by The Spectator, Kevin Hague asks why the Scottish Government’s “scene-setter” paper - the first instalment of its new independence prospectus - does not talk about Scotland.

The Scottish Government has published the first instalment of their new independence prospectus, a paper with the remarkably verbose title "Building a New Scotland - Independence in the modern world. Wealthier, happier, fairer: why not Scotland?"

Scottish Government resources have been diverted away from the tedious day-to-day business of running the country to produce this paper and Scotland’s First Minister has taken time out from her busy schedule of talking about independence to hold a press conference to announce that "it is time to talk about independence", so I felt duty bound to sit and study what has been produced.

The further I got into the paper, the more I found myself asking the same question as posed by the paper’s title: why not Scotland?

There are 22 figures, 11 charts, 6 boxes and 1 table in the report and not one of them includes any data relating to Scotland. This is an extraordinary state of affairs: a report written by the Scottish Government which we are told is "designed to contribute to a full, frank and constructive debate on Scotland's future" fails to include any data about Scotland.

We are implicitly being asked to accept that Scotland’s performance against any of the metrics charted in the paper are in no way the responsibility of the Scottish Government which the SNP has led for the last 15 years.

Instead of the robust analysis and sound logical reason we might expect from a paper produced by Scottish Government civil servants, we are instead offered pages upon pages of lazy rhetorical assertion.

The introduction offers a rather feeble attempt to justify this approach (at least in relation to fiscal data) by blithely asserting that the fiscal position of Scotland within the United Kingdom "tells us nothing about how Scotland would perform as an independent country and is, in any case, an argument for change, not against it."

We are explicitly being asked to believe that data about the scale of our existing tax base (the tax paying workers, consumers, households and businesses in Scotland today) and the cost of delivering the public services Scots currently receive (pensions, social welfare, healthcare, education, transport etc.) tells us nothing about how our economy would perform after independence.

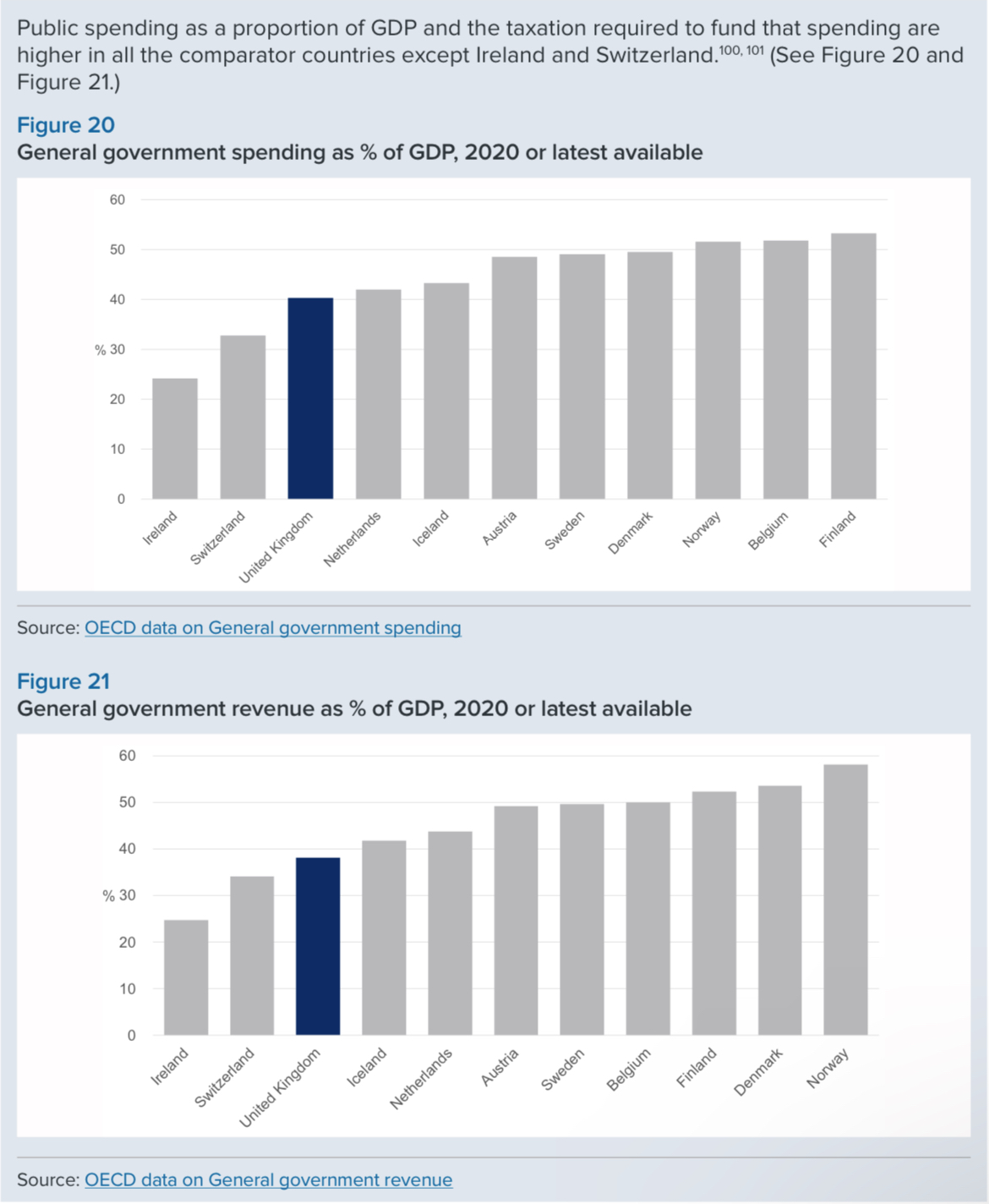

We are also expected to accept the unsubstantiated and nakedly political assertion that any data that does exist is "an argument for change, not against it". To understand how lazy that statement is - and illustrate how poorly the paper presents data - we just need just to look at two charts they offer to compare levels of tax and spend between their chosen comparator countries:

The data is mislabelled (it in fact quite sensibly shows 2019 pre-pandemic data) and, as the paper itself notes in an earlier footnote, showing data for Ireland on an unadjusted GDP basis is meaningless. But the most obvious flaw with these charts is, as with all the others, Scotland is not included.

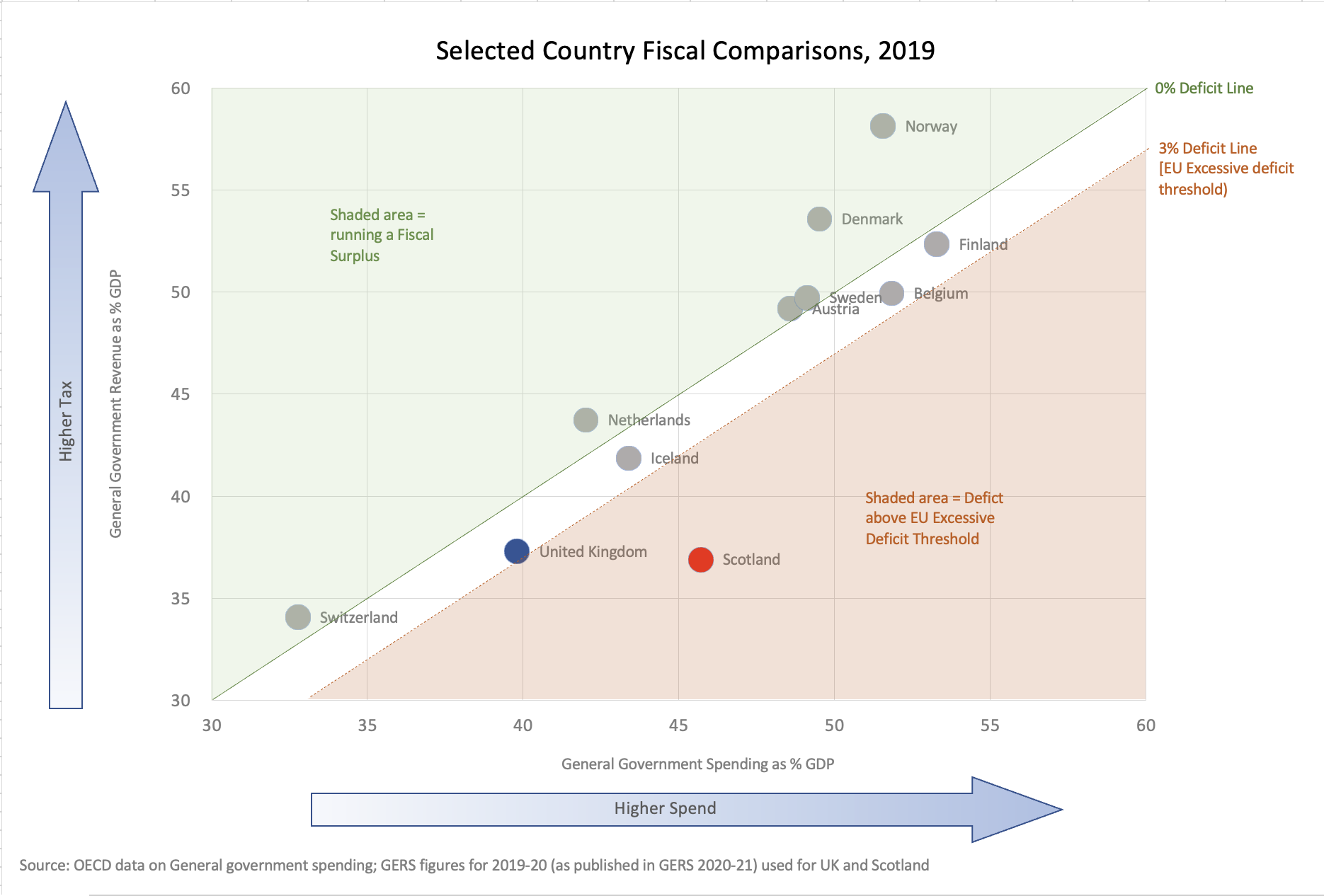

It's not difficult to present this same data more clearly and to add the data for Scotland (which the Scottish Government itself publishes):

This presentation makes clear what the bar charts in the paper do not: higher taxation is obviously correlated with higher spending and the paper’s chosen comparator countries were all below the EU's excessive deficit threshold in 2019.

Adding the known data for “Scotland in the UK” shows that it enjoys far higher levels of public spending than the UK overall but bears basically the same tax burden. This is an illustration of the fact that Scotland gets a higher share of spending than its share of revenue generated or, to couch this in terms nationalists like to use, Scotland gets back more than it sends to Westminster.

Remember: without including any fiscal data for Scotland, this Scottish Government paper asks us to take on trust the assertion that the fiscal data is "in any case, an argument for change, not against it".

By moving beyond ideologically motivated assertion and looking at the actual data it becomes clear that the fiscal data can be used to make a compelling, economically rational argument for Scotland remaining in the UK.

This more insightful data presentation also makes clear the challenge faced by any prospectus trying to make a credible economic case for Scottish independence: to show how an independent Scotland’s balance of tax and spending would change to achieve a sustainable fiscal position.

You need to search hard to find it, but the paper does touch on this question when it rather plaintively asks: "Why are most of the comparator countries able to sustain relatively high spending over the long-term?"

In fact, by including data the paper chose not to include, we have shown that Scotland already enjoys "relatively high spending" as part of the UK. This chart also makes the answer to that question blindingly obvious: by having relatively high taxes.

The data provided shows that the comparator countries chosen by the papers’ authors are all fiscally prudent. In normal times they only allow spending to exceed revenue within the constraints of the EU's 3% Excessive Deficit threshold.

So if an independent Scotland is follow the chosen comparator countries’ fiscal models then tax revenues would need to dramatically increase or public spending would need to be cut.

The answer given by the Paper hints towards tax rises, albeit indirectly. We are told that "Evidence suggests that higher confidence in government is correlated with higher levels of willingness to comply with taxes ..." and offered this quote from an article in support of higher tax economies: "Far from impeding prosperity, it is high-growth countries that tend to have a larger share of tax revenues in [sic] GDP"

The SNP's own Sustainable Growth Commission previously recommended controlling the deficit through austerity (i.e. by cutting public spending as a share of GDP). This latest paper strongly hints towards an independent Scotland increasing tax revenues as a share of GDP.

In the context of the annual debate around Scotland’s fiscal position within the UK (aka the GERS debate) some of us have been saying for a long time that, were Scotland to become independent, a combination of tax rises and public spending cuts would be an inevitable consequence. It seems the Scottish Government might be edging towards the same conclusion.

Although this paper doesn't address the issue head-on, buried within it is a tacit admission that only by generating higher taxes could Scotland sustain the higher spending we already receive as part of the UK.

Whether tax rate increases would be effective is perhaps a debate for another day; but if a lower tax regime is just across the mainland border and another even lower tax regime exists in neighbouring Ireland, it's not hard to imagine what would happen to the tax base in an independent Scotland if corporations and high earners were squeezed with higher taxes.

We wait with interest to see if future papers in this series address the fiscal deficit question using actual numbers for Scotland's economy and with realistic estimates for the scale of tax rises and spending cuts that an independent Scotland would have to bear to achieve a sustainable fiscal position.

There are many other problems with this paper but I can’t close this piece without referring to the report’s schizophrenic attitude to borders.

The paper repeatedly mentions that barriers to trade caused by Brexit will be economically damaging for the UK. Some of us may agree with that conclusion but, given the Scottish Government's argument for independence is predicated on re-joining the EU, the logical inconsistency here is obvious.

After decades of unfettered access to both the EU and the UK single markets, Scotland still exports more than three times as much to the rest of the UK than it does to the EU. If an independent Scotland were to join the EU, those barriers to trade would shift from affecting the 19% of Scotland's exports that go to the EU and instead impact the 60% of exports that go to the rest of the UK.

The evidence of economic damage being caused by EU/UK trade friction is, like the actual fiscal data for Scotland within the UK, an argument against separation, not for it.

This piece was first published by The Spectator, on 18th June 2022.

Please log in to create your comment