THE MCCRONE MYTHOLOGY

26 February 2025

A 1974 memo written by Scottish Office economist Gavin McCrone has acquired a mythical status for Scottish nationalists. But how much of the mythology is true?

SNP poster (1974) photographed by author at National Library of Scotland.

1974 was a tumultuous year in British politics. The winter of 1973-74 had been marked by an escalating stand off between Edward Heath's Conservative government, which was wrestling with high inflation, and striking coal miners, who were determined to secure better pay. Heath implemented the Three-Day Week to conserve supplies of coal (Britain was then heavily dependent on coal-fired power stations for electricity). But by February 1974 the situation had become untenable. Heath called a general election and famously asked voters to decide: "Who governs Britain?"

During the lull in activity which always occurs in a general election campaign, Scottish Office economist Gavin McCrone wrote a memo on North Sea oil for the incoming government. For 30 years, that memo was largely forgotten, along with countless similar documents which are part and parcel of the normal process of government, and not intended for publication.

But that particular memo was eventually published, in 2005, as a result of a Freedom of Information request. Since then it has acquired a mythical status for Scottish nationalists. In what is now an annual tradition, The National newspaper marks the anniversary of the memo by devoting a week’s worth of coverage to all sorts of fantastical stories built around the McCrone mythology.

Front pages of The National, celebrating "McCrone Day" in 2019, 2020, 2023, and 2024. They took 2021 off for Covid and 2022 because the Russian invasion of Ukraine had happened 3 days earlier.

There are three elements to the McCrone mythology:

-

Hush up

-

Huge forecast oil revenues

-

Implications for Scottish independence

The first is easy to deal with. Briefings for ministers, written by civil servants, are never intended for publication. Not then, and not now. They only ever see the light of day through Freedom of Information requests. Gavin McCrone made this point in his 2022 book on the economics of Scottish independence:1Gavin McCrone, After Brexit: The Economics of Scottish Independence (2022), p. 116

“There have been suggestions in the press that my paper was suppressed or in some way hushed up. This was not so. It was a confidential briefing for Ministers and never intended for publication, just as other briefing papers for Ministers are confidential.”

The McCrone memo was dated 27th February 1974 (the day before the election) and copies were presumably dropped into a handful of those famous red boxes, along with numerous other papers, for ministers to read once a new government had been formed.

The second and third elements of the mythology are meant to convince us that even if there was no conspiracy to hush up the memo itself, the information it contained was kept from the public.

However, the third element is as flimsy as the first. What the oil revenues forecast by McCrone implied for a potentially independent Scotland - in terms of fiscal surpluses and strength of currency - followed automatically from their magnitude. Any mainstream economist of the era would have agreed with McCrone’s observations on these points. But, according to the mythology, the expected magnitude of the revenues was concealed, to prevent the joining of the dots.

This is the very heart - the core element - of the alleged McCrone conspiracy. But is it true?

To answer that question we must pick up the story in 1974. The general election on 28th February resulted in a hung parliament, with the Labour Party winning 301 seats to the Conservatives 297. Edward Heath could not agree terms with the Liberal or Ulster Unionist parties to form a coalition government, which meant the Labour leader, Harold Wilson, became Prime Minister (for the second time).

His minority government was clearly not a sustainable one and just seven months later, in an attempt to win a majority and achieve stability, Wilson called another general election. That election was held on 10th October 1974 and resulted in a Labour majority of three seats.

One of the first priorities of the new government was to pass legislation giving clarity on taxation policy to the oil companies who would bring the as yet undeveloped North Sea discoveries to production - the very same issue which is the heart of the McCrone mythology.

This is what McCrone had forecast in his memo, with the key figures highlighted in bold:2https://www.thenational.scot/business/17461406.westminster-doesnt-want-read-mccrone-report-full/

“The DTI estimates of last summer showed that total Government revenue following adoption of these measures would have been between £800m. and £1,200m a year in 1980 depending on the system used and the prices prevailing in 1980; today, following the huge increase in international oil prices of recent months the corresponding figures are in the range of £1,500m to over £3,000m. Thus, all that is wrong now with the SNP estimate is that it is far too low; there is a prospect of Government oil revenues in 1980 which could greatly exceed the present Government revenue in Scotland from all sources and could even be comparable in size to the whole of the Scottish national income in 1970.”

On 25th February 1975, within a year of McCrone making this forecast, the Paymaster General, Edmund Dell, made a statement in the House of Commons on Petroleum Revenue Tax (in other words: the taxation of North Sea oil).

One of the questions following the statement was asked by Gordon Wilson, the MP for Dundee East and the SNP’s energy spokesperson (he would become its leader in 1979). Wilson asked for the government’s estimate of the revenues to be expected. This was the Paymaster General’s answer, as recorded in Hansard:3https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1975-02-25/debates/3e67e812-c3d6-4b82-bb33-614f7f7ceeab/NorthSeaOil#contribution-e599df9a-d62b-47ee-a978-dc6aaa73a4f0

“The hon. Member asked for an estimate of revenues on the basis of certain figures of oil production in – I take it – the 1980s. He will understand that in the early years the revenue from North Sea oil will be relatively small but growing fast. In the early 1980s, at a figure of 100 million tons, it should be £2,000 million or £3,000 million. Of course, the higher the production the greater the consequent revenues. However, all figures in this respect must be treated with some caution because they depend, first, on the price of oil and, secondly, on the cost of exploration and development. I therefore suggest to the hon. Gentleman that we wait to see what we get before relying on it too much.”

Yes. That’s right: the Paymaster General gave parliament the same forecast that McCrone had included in his memo. Actually a slightly higher forecast, since the bottom end of the range had increased. And less than a year after McCrone’s memo was written.

The figures were not attributed to McCrone, but civil servants are never named in such circumstances, and he was then an anonymous government economist who nobody (beyond some former colleagues in academia) would have heard of anyway.

Nevertheless, the McCrone forecast of huge oil revenues was now in the public domain, and his figures proved to be quite accurate - oil revenues in 1980 were close to the middle of McCrone's forecast range. Bit of a problem for the mythology.

But all sorts of things are said in parliament, and this was long before television cameras were allowed in. Perhaps these figures were missed by the reporters in the press gallery, and the public never found out?

Here is the front page of the next day’s Times:

And The Daily Telegraph:

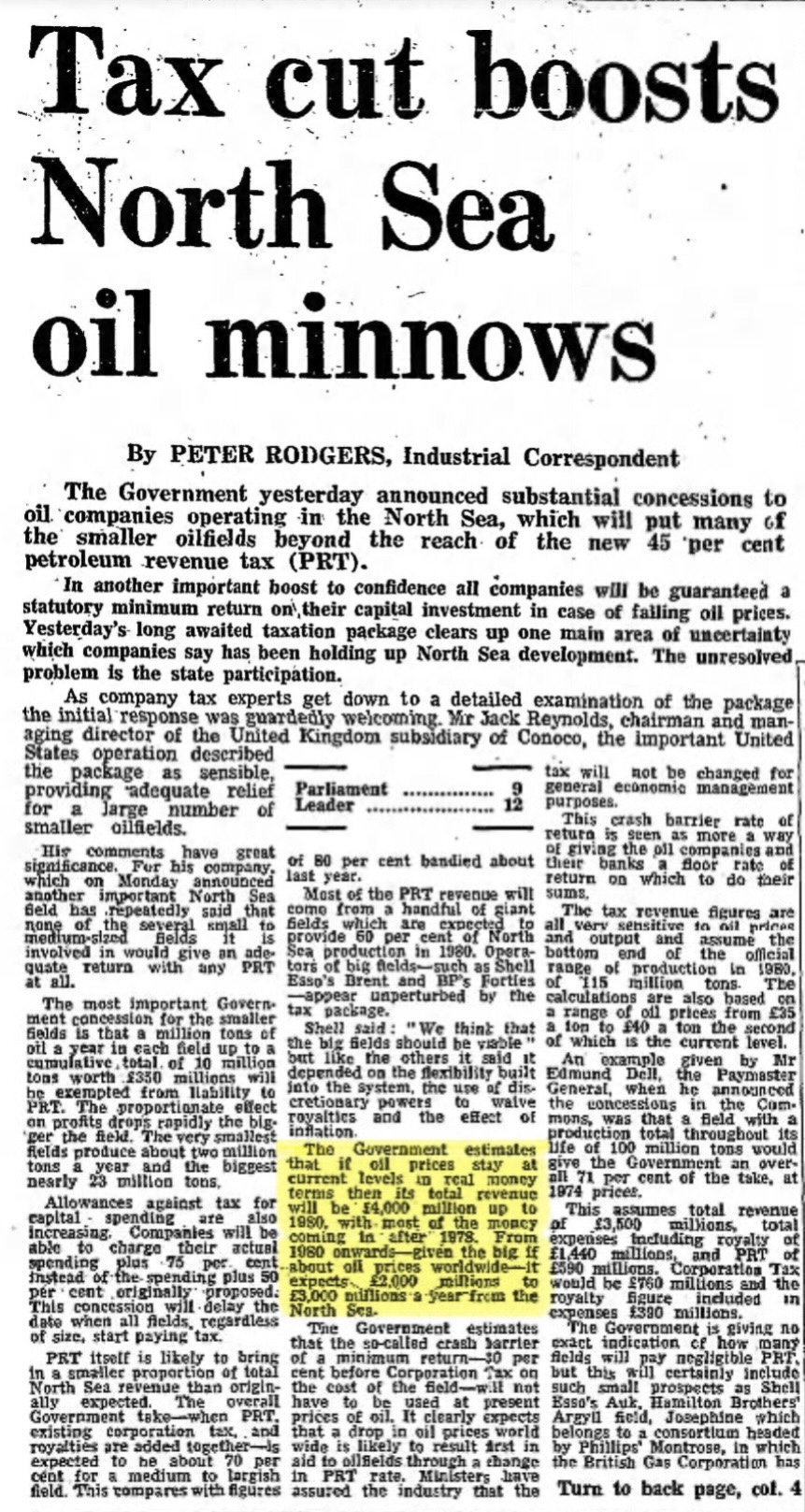

The Guardian didn’t put the figures in the headline...

... but they were in the copy:

Maybe the Scottish newspapers missed it?

Nope.

The Scotsman reported some additional information, provided by the Treasury, which included more detail than was stated in parliament:

The Daily Record didn't put the story on the front page, but the whole of page 2 was devoted to it:

And the Record took a slightly different tack on reporting the revenue forecast, talking about the per day amounts expected from just the Forties field, which was known to represent about a quarter of the North Sea discoveries. So this was completely consistent with the McCrone numbers.

Anyway, the point has been made: McCrone’s numbers were everywhere. The mythology says that even if the memo itself wasn’t suppressed by a conspiracy, those numbers very much were. And that mythology is false.

So how did it gain such traction?

An interview with Denis Healey, who was Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1974 to 1979, is significant. It was published by Holyrood Magazine in May 2013, and one quote in particular was reported very widely:4https://www.holyrood.com/editors-column/view,still-raising-eyebrows_11042.htm

“I think we did underplay the value of the oil to the country because of the threat of nationalism but that was mainly down to Thatcher. We didn’t actually see the rewards from oil in my period in office because we were investing in the infrastructure rather than getting the returns and really, Thatcher wouldn’t have been able to carry out any of her policies without that additional 5 per cent on GDP from oil. Incredible good luck she had from that.”

These words were seized upon by Scottish nationalists as confirmation of a conspiracy uncovered 8 years earlier by the publication of the McCrone memo.

But notice how Margaret Thatcher is the central figure in Healey’s remarks.

When Edmund Dell, the Paymaster General, gave the McCrone numbers to parliament on 25th February 1975, Margaret Thatcher had only been leader of the opposition for two weeks. It took several years for her agenda - a radical remoulding of the British state - to take shape.

The coming oil revenues would clearly serve to buttress Thatcher’s plans, as well as to give succour to Scottish nationalism. For both reasons, Healey thought it unwise to talk too much about them - an understandable reticence when those revenues were beyond the horizon of the next election (they would not really begin to flow until the 1980s) and so were unavailable for him to spend.

Denis Healey said nothing in that interview which contradicted the historical record. We know the McCrone numbers were put into the public domain, and splashed across the front pages of newspapers, within a year of McCrone including them in his memo. Denis Healey making the perfectly understandable decision to avoid talking about something which was ammunition for his opponents is not a conspiracy or a cover up. It’s just politics.

One thing ultimately explains why McCrone continues to capture the imagination of a certain kind of independence supporter. And that is the first rule of modern day Scottish nationalism:

If the SNP fails, it is always Westminster’s fault.

If the SNP couldn't persuade a majority of Scots to support independence on the cusp of an oil boom, the cause must have been hobbled by foul play from Westminster. It's the only permissible explanation.

When the Freedom of Information Act came into force in 2005, it gave the SNP the opportunity to rewrite the history of the 1970s.

The humdrum truth of the matter - that by 1975 everyone was fully aware of the magnitude of revenues likely to flow from North Sea oil - was replaced with a narrative much more acceptable to Scottish nationalism: a conspiracy theory in which a malevolent Westminster hid the truth from the people of Scotland.

In fact, the people of Scotland had all the information about the coming oil revenues, years before they began to flow. And the SNP still could not persuade a majority of the electorate to vote for its nationalist agenda.

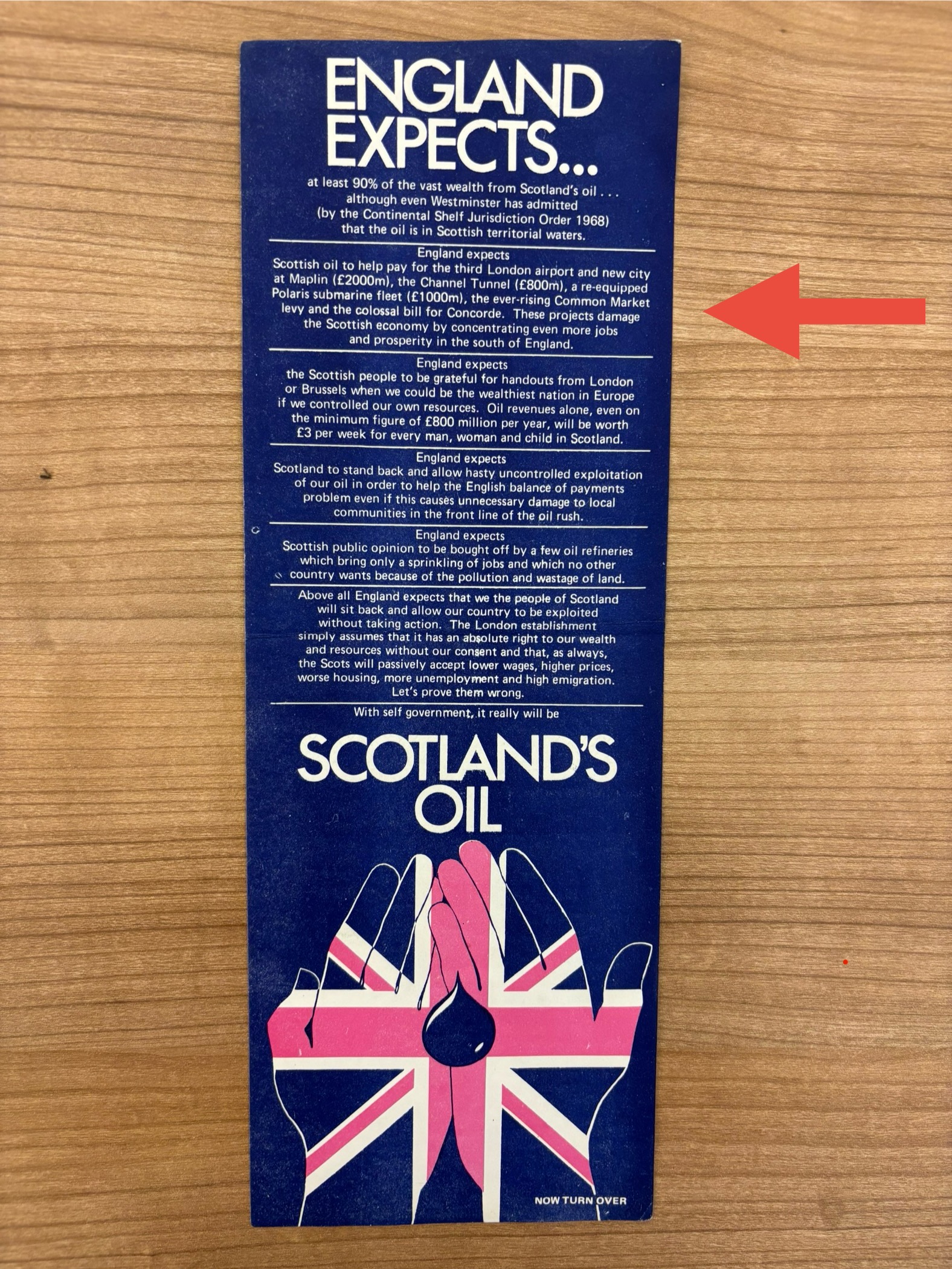

Examining election materials from the period gives an insight into why that might have been. This is a leaflet produced for Gordon Wilson's campaign in Dundee East at the February 1974 general election.

Photographed by author at the National Library of Scotland.

Notice the litany of complaints in the highlighted section: the SNP was railing against Britain's nuclear deterrent (when the Cold War was a long way from thawing), membership of the Common Market, the Channel Tunnel, even Concorde. (The Maplin project was a proposal to build a third London airport on reclaimed land off the coast of Essex, but it never actually happened - the project was cancelled in July 1974.)

We know from the 1975 referendum that a majority of Scottish voters were in favour of membership of the EEC. Scotland specific polling on 1970s attitudes to nuclear weapons is not readily available, but perhaps the typical voter was not as keen on unilateral disarmament as the SNP? And maybe Scots rather liked the idea of the Channel Tunnel, and saw the practical advantages of the British end landing in England?

The point is clear: voters had many reasons to reject the Scottish nationalism of the 1970s. Gavin McCrone said in his 1974 memo that expected oil revenues meant there was a credible economic argument for Scottish independence. But a credible argument is not automatically a popular one. Credibility and popularity are not the same thing.

It's also notable that the 1974 leaflet talks about oil revenues of at least £800m per year. This was the number mentioned by McCrone as being "far too low". But, as we have established, the government quickly made McCrone's higher forecast public, and this is evident from the SNP's manifesto for the 1979 general election:

![/image/IMG_6641[1].jpeg](/image/IMG_6641[1].jpeg)

Return to Nationhood: A summary of the ideology of Scotland's right to independence, the guiding principles of the Scottish National Party and an outline of its programme for self-government. 1979. Photographed by author at the National Library of Scotland.

By 1979, the expected oil revenues had narrowed down to the top end of McCrone's forecast range, and notably the 1979 manifesto made no reference to the figures having been concealed by Westminster. No reference was made to a cover up because there was no cover up. The McCrone mythology is a 21st century invention. It never happened.

And what was the outcome of the 1979 general election for the SNP? It won only 2 seats, losing 9 of the 11 it had held since October 1974. Its share of the vote collapsed from 30% to 17%. If having the McCrone figures was supposed to be the key to persuading voters to back the SNP's vision for an independent Scotland, the 1979 general election is decidedly inconvenient. The final nail in the coffin of the McCrone mythology.

Please log in to create your comment