FULL FISCAL ARITHMETIC

29 May 2025

Imagine the Scottish Government gets what it’s asking for: full fiscal autonomy. What happens then? And what is the significance of the so-called fiscal transfer? This short piece answers these key questions.

In June 2015, MPs rejected an SNP amendment to the Scotland Bill (on more powers for the Scottish Parliament) which would have paved the way for full fiscal autonomy in Scotland. The SNP, having pursued the policy with some vigour since losing the 2014 independence referendum, quietly dropped the idea. There was no mention of full fiscal autonomy in any subsequent SNP manifesto, for Westminster or Holyrood elections.

So it came as a significant surprise when it was recently resurrected. In a letter providing evidence to the House of Commons Scottish Affairs committee inquiry into the Financing of the Scottish Government, Shona Robison said this:1https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/46344/documents/233832/default/ “Within the current constitutional settlement, full fiscal autonomy would be the Scottish Government's preferred option.”

This development may even have surprised some of her cabinet colleagues. The Scottish Government subsequently admitted (in a Freedom of Information response2https://x.com/staylorish/status/1922702205745848388?s=46&t=y9v1mXDn2DQJqjCpgZcKXg) that it did not know when John Swinney or Kate Forbes became aware of the contents of Shona Robison’s letter, and that: “The First Minister and the Deputy First Minister and Cabinet Secretary for Economy and Gaelic were not required to clear the contents of the letter before it was sent to the House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee.”

Even more shockingly, another Freedom of Information response revealed that:3https://x.com/staylorish/status/1922702218844647824?s=46&t=y9v1mXDn2DQJqjCpgZcKXg “the Scottish Government has not undertaken any analysis on the implications of full fiscal autonomy for the Scottish Government's budget”

If there was a suspicion that Shona Robison had accidentally adopted this extremely radical policy, it was nevertheless confirmed to be the government’s position on 14th May 2025. Angus Robertson, answering a question from Michael Marra in the Scottish Parliament, said this:4https://www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/official-report/search-what-was-said-in-parliament/meeting-of-parliament-14-05-2025?meeting=16413&iob=140181#orscontributions_M16185E422P758C2686210

“Until the people of Scotland can choose a different constitutional arrangement, moving to full fiscal autonomy would create a fairer system, protecting public services and allowing investment in our economy. The Scottish Government stands ready to engage at any point with the United Kingdom Government on substantial new fiscal powers for Scotland, following which we will model the impact of potential policy choices.”

A week later, Shona Robison appeared before the Finance and Public Administration Committee of the Scottish Parliament, and struggled to explain why the government was pursuing full fiscal autonomy without knowing anything, or doing any work, on what the implications might be. The relevant exchanges can be watched here.

Full Fiscal Arithmetic

Full fiscal autonomy means fundamental changes occur to both sides of the Scottish Government’s budget: revenue and expenditure.

Revenue increases because all taxes generated in Scotland flow directly to the Scottish Government.

But expenditure also increases. All spending attributable to Scotland which was previously covered by the UK Government must now come out of the Scottish Government’s own expanded budget. Things like state pensions must be paid directly by the Scottish Government. And other things, still administered by the UK Government (like defence, foreign affairs, and the interest expense on legacy national debt) must be paid indirectly, in the form of an agreed payment to the UK Government.6“From the tax revenue raised in Scotland, a direct payment would be made for those responsibilities which remain reserved to the UK Government, including defence, security and foreign policy.” Extract from Shona Robison’s letter to the House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee, 16th January 2025

What do both sides of the expanded budget look like? This question is of profound importance and is why the Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland (GERS) report is so crucial. It answers that question by telling us what a fiscally autonomous Scottish Government’s budget - both sides of it - would have looked like in recent fiscal years.

This is not the place to debunk Scottish nationalist complaints about GERS. That debunking has been done many times before, and suffice to say: the complaints are bogus. Of course GERS figures are calculated under the current constitutional arrangements. That’s the point: a fiscally autonomous (or independent) Scottish Government could not sustainably function with the revenues and expenditures reported in GERS. It is incumbent on SNP politicians to explain what changes they would implement to put things on a stable footing. Arm-waving talk about “levers” is not good enough. Which levers? And in which direction?

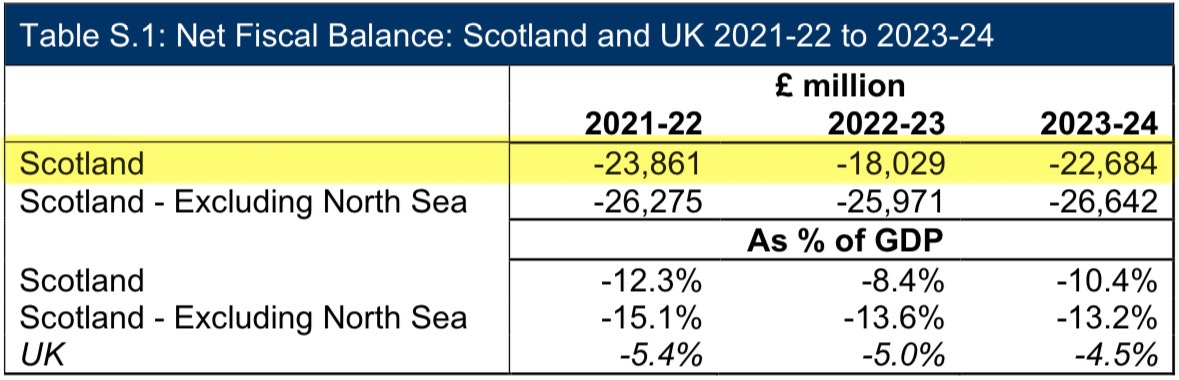

The predicament the Scottish Government creates for itself with full fiscal autonomy is quite simple: the expenditure side of its budget increases by far more than the revenue side. The extent to which a fiscally autonomous Scottish Government’s budget would not have balanced in the last three fiscal years (that we currently have data for) is show in this table:6https://www.gov.scot/publications/government-expenditure-revenue-scotland-gers-2023-24/

Assuming the taxation of North Sea oil & gas would be included in a full fiscal autonomy settlement, the first line in the table is key. It tells us that in 2023-24, a fiscally autonomous Scottish Government would have spent £22.7 billion (10.4% of Scotland’s GDP) more than it generated in revenues.

So why isn’t £22.7 billion the fiscal transfer? Well, arguably it is a more important number than the fiscal transfer. But here is why the two numbers are not the same.

The fiscal transfer is calculated by making an implicit assumption about a fiscally autonomous Scottish Government’s ability to borrow. It assumes that in any given fiscal year, the Scottish Government could have borrowed the same percentage of Scottish GDP (and on the same terms) as the UK Government borrowed relative to UK GDP.

This is less complicated than it sounds, and an example calculation illustrates just how straightforward it really is.

In 2023-24, the UK Government’s net fiscal balance (from the previous table) was -4.5% of GDP. This is the amount the UK Government as a whole borrowed in that fiscal year. So the assumption is that a fiscally autonomous Scottish Government could have done the same, relative to Scotland’s GDP.

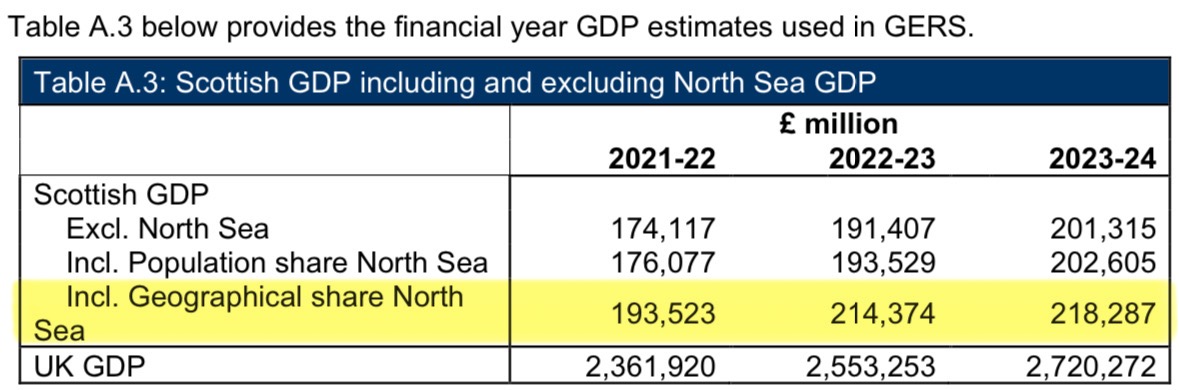

Here are the relevant GDP figures for Scotland:

4.5% of £218.3 billion is £9.8 billion.

The difference between £9.8 billion and £22.7 billion is £12.9 billion, and that is the fiscal transfer.

It answers this question: if we assume that a fiscally autonomous Scottish Government could have borrowed to the same extent (relative to GDP), and on the same terms, as the UK Government did, how much more would it have needed to borrow to cover all the expenditure it would have been responsible for?

But it’s important to emphasise that full fiscal autonomy would actually have created a £22.7 billion hole in the Scottish Government’s budget in 2023-24.

The fiscal transfer concept effectively partitions that hole into two parts: one part which it says would have been easy to fill, because it’s proportionately the same size as the UK Government’s fiscal hole. And the second part (the part labelled as the fiscal transfer) which would have been more challenging, because it would have required borrowing over and above the level of UK Government borrowing.

But this story is clearly not a realistic one. In reality, a fiscally autonomous Scottish Government has one large fiscal hole to fill, not two smaller ones which debt markets would look at separately.

In 2023-24, to avoid having to cut public spending or increase taxes, a fiscally autonomous Scottish Government would have needed to borrow £22.7 billion (10.4% of Scotland’s GDP) from the bond market.

But the bond market is an unforgiving judge of fiscal arithmetic. Just ask Liz Truss, whose mini-budget fiscal surprise was a comparatively modest 2% of GDP. The bond market needs to know the total amount of borrowing you are planning before it will lend you anything at all.

If a fiscally autonomous Scottish Government signalled that it was planning to borrow around 10% of GDP annually, the bond market’s response would be inevitable and unprintable.

If the Scottish Government signalled that it planned to borrow around 4.5% of GDP, the bond market would say: well that’s a bit more realistic, but we’ll want a higher rate of interest than UK Government debt. And that higher rate could easily make the borrowing unaffordable.

The most likely scenario is that the Scottish Government would have to keep borrowing at very modest levels in the early years of full fiscal autonomy. Perhaps just 1-2% of GDP.

So the fiscal transfer of £12.9 billion in 2023-24 was really the best case (but wholly implausible) scenario for the size of the hole full fiscal autonomy would have created in the Scottish Government’s budget.

The true size of the hole would have been somewhere between £12.9 billion and £22.7 billion, and realistically much closer to the upper end of that range than the bottom. And this means that £12.9 billion would have been the minimum amount of spending cuts or tax rises that full fiscal autonomy would have compelled the Scottish Government to implement.

The UK Government should take seriously the Scottish Government’s request for full fiscal autonomy, and ask it to answer the following questions:

-

What does the Scottish Government believe it could sustainably borrow, annually, as a percentage of Scotland’s GDP? (10%, or anywhere close to it, is not a credible answer.)

-

What combination of spending cuts and tax rises would the Scottish Government utilise to bridge the remainder of the gap which currently exists between revenue and expenditure?

Please log in to create your comment