ZONAL PRICING: WHAT HAPPENED?

13 July 2025

Zonal pricing of electricity is not going to happen. At least not any time soon. The UK Government’s decision, part of the Review of Electricity Market Arrangements (REMA) process, which it inherited from the previous government, brings to an end three years of intense lobbying from supporters and opponents of zonal pricing.

Which camp did the SNP belong to? And why? Did some of the lobbying exaggerate the truth? And does the SNP have a coherent vision for electricity market reform? This piece will attempt to answer these questions.

The problem

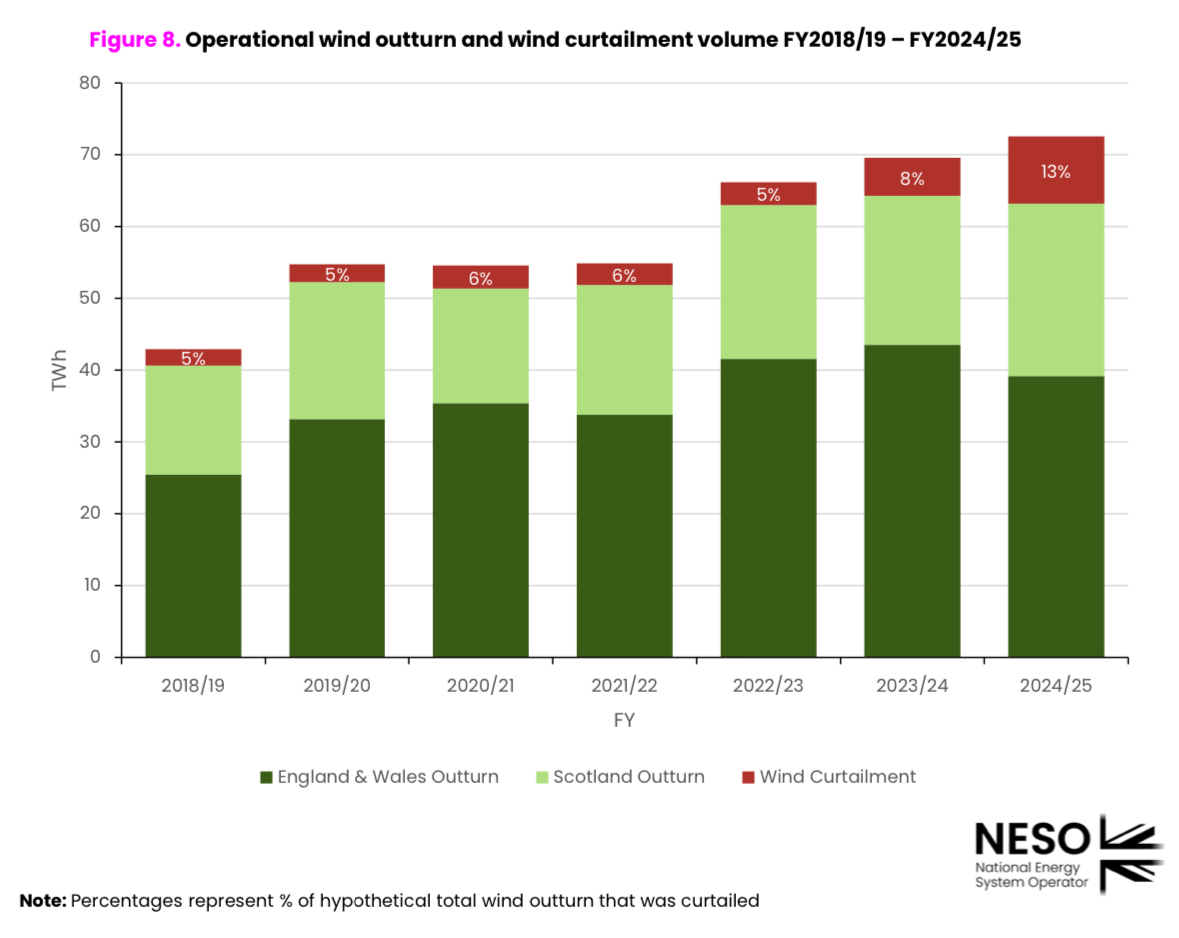

If you want to understand how the GB electricity market works (and sometimes doesn’t work) this chart is a good place to start.1https://www.neso.energy/document/362561/download

Some of what it tells us is obvious. The output of GB wind farms has been growing steadily over recent years. Most of that output is located in England and Wales, but a sizeable chunk is in Scotland.

And it also reveals less obvious things. Wind curtailment (shaded red) has been growing rapidly, especially in the last few years. This is the output wind farms could have delivered, but were prevented from doing so because of insufficient grid capacity to connect the output with consumers. In these circumstances, wind farms are paid so-called “constraint payments” - they are paid to turn themselves down.

These payments are controversial and this probably explains why NESO (the National Energy System Operator) does not provide easily accessible data on exactly where curtailment is happening, and how much individual wind farms are receiving to reduce output.

But we do know that the overwhelming majority of curtailed wind output occurs in Scotland. Carbon Tracker and the Renewable Energy Foundation are diametrically opposed organisations - evangelists and sceptics on renewable energy - but they agree on one thing: the former puts Scotland’s share of curtailed wind output at 95%2https://carbontracker.org/britain-wastes-enough-wind-generation-to-power-1-million-homes/, the latter at 98%.3https://www.ref.org.uk/ref-blog/384-discarded-wind-energy-increases-by-91-in-2024

And if those red bars are essentially all attributable to Scotland, you only have to eyeball the chart to see that roughly a quarter of the potential output of Scottish wind farms was curtailed in 2024/25.

There is no great mystery to why this is happening. When the wind really blows, there simply aren’t enough customers in Scotland to consume all the electricity produced by Scottish wind farms. And nor is there enough grid capacity to deliver all the excess electricity to England, where it could have been consumed.

A case study: Moray East offshore wind farm

Although it is difficult to obtain the data on how much any given wind farm receives in constraint payments, some information can be found in accounts filed at Companies House.

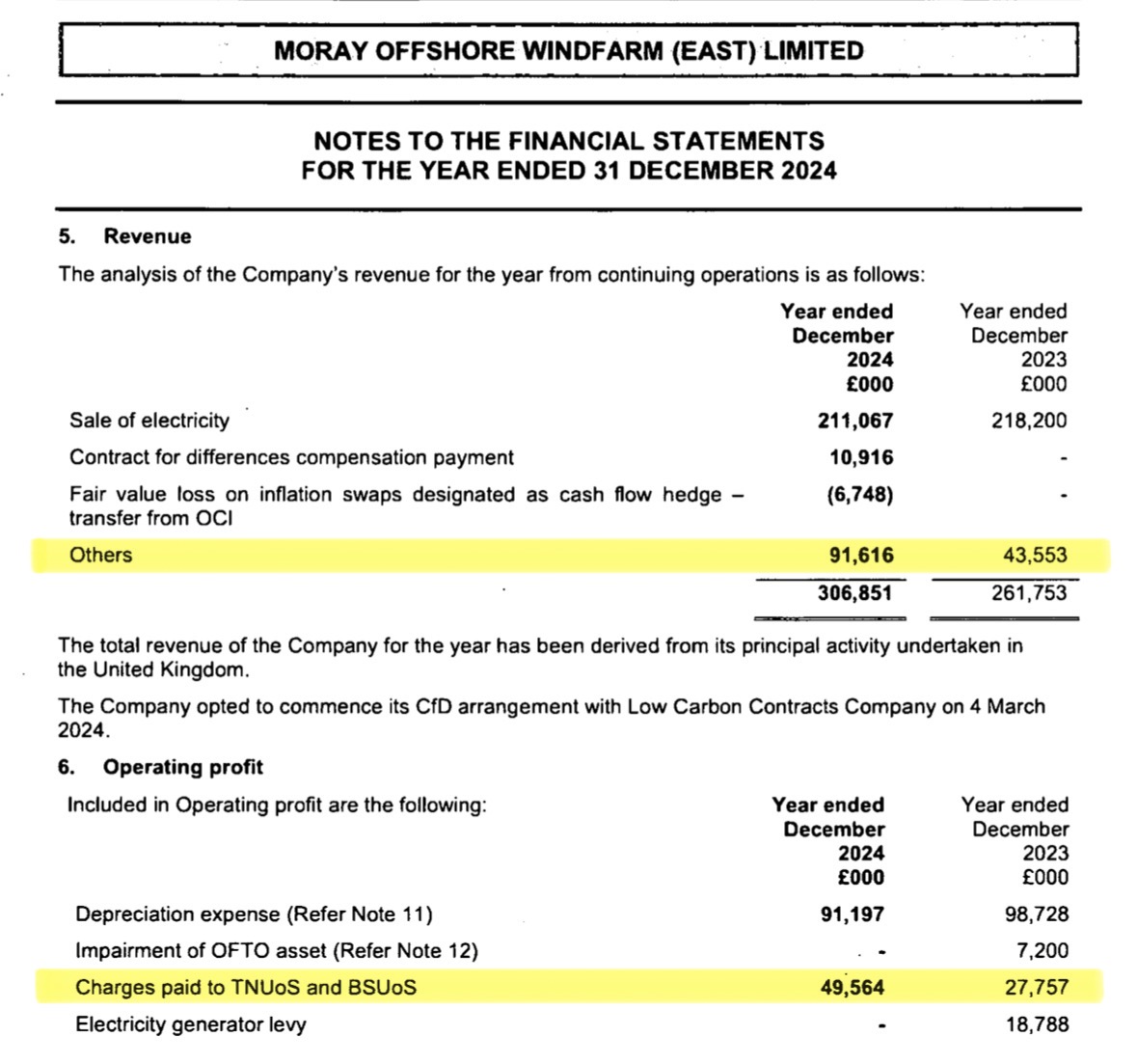

The Moray East offshore wind farm is the second largest operational wind farm in Scotland. Here is a pertinent extract from its most recent accounts (for calendar year 2024):4https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/07101438/filing-history

Notice the first highlighted line - labelled “Others”. What could this be? It’s not spelled out in the accounts, but this is likely to be almost entirely comprised of constraint payments. After being paid to generate electricity, being paid not to generate electricity is the only other meaningful way a wind farm can earn revenue.

And for the Moray East offshore wind farm, it’s a very significant source of revenue: almost a third of total revenue in 2024.

The cost of constraint payments is socialised across all GB bill payers. So, although curtailment is pretty much always caused by Scottish wind farms, the cost of dealing with it is paid mostly by consumers of electricity in England.

A well-worn Scottish nationalist grievance goes something like this: “we send electricity to England and get nothing in return”. For a high and rising share of the time, the complete opposite is true: “England sends money to Scotland, and gets no electricity in return.”

Nobody disputes that the status quo, as exemplified by the accounts of Moray East, is suboptimal. To be paying wind farms vast sums of money to do nothing is clearly a dysfunctional situation. Something needs to be done about it.

And something, at least, is already being done about it.

What we already do: transmission charges

The second highlighted line in the Moray East accounts is “Charges paid to TNUoS and BSUoS”. These are Transmission Network Use of System (TNUoS) and Balancing Services Use of System (BSUoS) charges.

In Scotland, the former is typically the larger of the two charges, and also the most controversial.

TNUoS charges pay for the grid: they fund the maintenance of what already exists, and also the construction of new grid - the additional power lines which unblock grid bottlenecks.

TNUoS charges are paid both by generators (ie big energy companies) and by consumers (commercial users of electricity and households). The split is roughly 20% of TNUoS paid by generation and 80% by consumers.

In Scotland, the TNUoS tariff for generation is higher than for generators anywhere else in GB. And for consumers, the opposite is true: the TNUoS tariff is lower in Scotland than anywhere else in GB.

This is perfectly logical and fair: generators located in Scotland exacerbate the grid constraint problem. Consumers located in Scotland ameliorate it. The greater the demand for electricity in Scotland, the smaller the need to curtail the output of Scottish wind farms.

Higher TNUoS tariffs for generators in Scotland compress profit margins for the owners of those assets. There is no direct impact at all on ordinary consumers of electricity in Scotland.5There is an indirect impact, via the wholesale price of electricity, since the higher cost base of Scottish wind farms becomes a factor in CfD auctions. But this impact is exactly the same for all GB consumers, inside or outside Scotland, because CfD costs are fully socialised. But Scottish consumers do directly benefit from the lower TNUoS tariffs paid by consumers.6https://x.com/staylorish/status/1641053542914899972?s=46&t=y9v1mXDn2DQJqjCpgZcKXg

The SNP has long argued that TNUoS tariffs structurally (and unfairly) disadvantage generators in Scotland. The Moray East accounts illustrate the flaw in this argument.

Look again at both of the highlighted lines from the accounts. If we assume the second line is almost entirely TNUoS charges, Moray East was paid about £90 million in 2024 not to generate electricity, and asked to hand about half of that amount back, to help maintain and expand the grid. (In truth it will have been less than half, because that line item won’t have been entirely TNUoS charges.)

Moray East demonstrates in microcosm something which is true of the system as a whole: the GB electricity system gives huge amounts of money to Scottish wind farms to sit idle, and claws back only a fraction of that money, to help solve the problem.

That claw-back mechanism, via transmission charges, is one solution to the problem of escalating constraint costs. It is a solution which already exists, but arguably does not go far enough.

Of course the owners of generation assets in Scotland argue that it goes too far - they are simply lobbying for their own commercial interests. And the SNP has chosen to swing behind that lobbying effort. It too would like Scottish wind farms to be asked to hand back an even smaller slice of the revenues they earn for not generating electricity.

What we might have done: zonal pricing

To understand how zonal pricing could have helped to solve the problem of constraint costs, we first need to understand a little more about how the problem arises.

At all times, NESO must ensure that just the right amount of generation is running to match demand (since we have only a very limited ability to store electricity at scale). It does this by dividing up the day into half-hour segments, and effectively running a reverse auction for each settlement period.

Generators tell NESO what price they will accept for output (which will reflect their short-run marginal costs) and NESO works its way up from the lowest to the highest priced generators, until it has scheduled for dispatch the right amount of generation to match expected demand.

There is just one wholesale market price for the whole GB electricity market, and that price is set by the final generating unit to be scheduled for dispatch. Whatever price it demanded is the price that everyone gets.

Wind and solar have short-run marginal costs of zero. So when the weather cooperates, those assets will be scheduled for dispatch first. The final (and therefore most expensive) generating unit to be scheduled is usually a gas-fired generator, which is why the gas price typically plays a key role in setting the wholesale market price of electricity.

Critically, all of this happens without any consideration being given to whether the generators being scheduled for dispatch can actually be connected with the demand they have been matched with. This sounds kind of mad. And it kind of is.

Only after generators across GB have been scheduled for dispatch (for a given settlement period) does NESO consider whether the grid can cope with the distribution of generation it has scheduled.

Increasingly often, it cannot. And this is almost always because Scottish wind farms have been scheduled, despite being the wrong side of the grid bottleneck between Scotland and England, meaning a significant portion of their output cannot get to where it is required.

This is where constraint payments come in. NESO has to pay scheduled Scottish wind farms to turn their output down. And at the same time, on the other side of the grid bottleneck, it has to pay flexible generators (usually gas-fired plants) to turn their output up. And because those gas-fired plants know they are being called on as a last resort, they can (and often do) demand very high prices for their gap-filling output.

These two effects - paying wind farms to turn down and paying for gas plants to turn up - are what drive constraint costs. And remember: these costs are socialised across all GB bill payers. Everyone pays for them, no matter where they live.

Zonal pricing would have divided the GB electricity market into zones demarcated so that pinch points in the grid, as far as possible, were between zones rather than within zones. The exact number of zones isn’t important for this discussion, but Scotland would probably have contained at least two (north and south Scotland).

Under zonal pricing, each individual zone would operate in the same way as the system currently works for the whole of GB. In other words: each separate zone would schedule for dispatch its own generating units to match its own demand. And each zone would therefore have its own wholesale market price, reflecting the most expensive generator required to meet demand.

It would still be possible for generating units to sell output in other zones, but this would depend on securing access rights (at a price) which reflected the actual availability of grid capacity between zones.

Because the whole of GB (on a zone by zone basis) would be scheduling for dispatch in a way which recognised grid constraints before rather than after scheduling a generating unit, the problem of scheduling a unit and then finding it couldn’t actually be utilised would be greatly reduced (although not entirely eliminated - it would still happen occasionally).

The “turn down” component of constraint costs - largely payments to Scottish wind farms - would have been expected to fall. And the “turn up” component should have fallen too. This is because gas-fired plants in high demand zones would have been scheduled for dispatch in the normal process of scheduling a zone, instead of as a gap-filling measure.

And because these costs are currently socialised across all GB bill payers, all zones in a zonal system would have benefited from these savings.

Exaggerated rhetoric

Because each zone would have had its own market price, and wholesale market prices are set by short-run marginal costs, zones with an excess of wind capacity would have seen market prices fall very substantially. They might often have been close to zero.

This is what led Greg Jackson (the CEO of Octopus Energy) to claim that Scotland would have had the cheapest electricity in Europe under zonal pricing.7https://x.com/scotnational/status/1812436670131658975?s=46&t=y9v1mXDn2DQJqjCpgZcKXg

Most people believed Jackson was talking about the electricity prices consumers actually pay. But he wasn’t. His claim was true only of wholesale market prices, reflecting short-run marginal costs. Consumers, however, have to pay the long-run costs of generation.

Nobody would ever build a wind farm if you could only sell the output at short-run marginal costs, which is why we have the CfD (Contracts for Difference) scheme. This guarantees wind farms an inflation-adjusted fixed price for output over a 15-year term, and Scottish wind farms would still have received these stabilised prices under a zonal system.

The wholesale market price would have fallen in Scotland, but CfD top-up payments - which stabilise revenue for wind farms - would have increased. Consumers of electricity in the Scottish zones would still have had to pay the stabilised price - that is the market price plus the top-up payment.

Wholesale cost savings would have existed for output falling outside the CfD regime, and these savings would have been more significant in the Scottish zones.

And it’s also important to remember that the costs of generation are just one element (and not even the majority) of customer bills. The grid has to be paid for too, and network costs would still have been an important component of bills under zonal pricing.

Taking all of these factors into consideration, the impact of zonal pricing on electricity bills in Scotland would have been relatively modest - something of the order of a 10% reduction. For electricity bills in Scotland to have fallen to amongst the cheapest in Europe would have required savings of 60-70%, and this was never on the cards under zonal pricing.

Close observers of this debate may have noticed that Octopus Energy did eventually stop making the “cheapest electricity in Europe” claim. These Islands pointed out that it was being widely misinterpreted, and the company accepted this.8This was established in meetings and correspondence between These Islands and Octopus Energy, and FTI Consulting, who were responsible for the modelling relied upon by Octopus.

Price signals

In the short-run, transmission charging and zonal pricing both act to compress the profit margins of generators in zones with excess wind generation and insufficient grid to get output to where it’s required. Transmission charging does it by clawing back “turn down” costs. Zonal pricing does it by trying to avoid paying those “turn down” costs in the first place.

These short-run impacts send price signals which have an impact in the long-run. Both transmission charging and zonal pricing should (all else equal) encourage generators to locate on the side of grid bottlenecks which puts them closest to demand, thereby minimising the amount of additional grid we need to build, and keeping total system costs as low as possible.

Zonal pricing would also have introduced a completely new price signal. There is a period at the end of a wind farm’s life - beyond the end of the 15-year CfD term - when generators sell electricity at merchant risk - ie at the wholesale market price, without subsidy or stabilisation.

This is the so-called “merchant tail”. It’s less important than the 15 years of stabilised prices, but it does matter in terms of generating acceptable returns for developers, and would have become less valuable in Scotland under zonal pricing, making some investments less likely to happen (which is ultimately why the UK Government decided against it).

Proponents argued that zonal pricing would have led to a leaner system, with a more efficient distribution of generation, requiring fewer new power lines, saving money for everyone. In other words: that reduced investments were a feature, not a bug.

Whether zonal pricing or transmission charging deliver the most effective price signals to make the system more efficient is effectively what the entire zonal pricing debate has been about. It is beyond the scope of this piece to get into the details of the relative pros and cons. For the purposes of this discussion, the important thing to recognise is this: you have to do one or the other.

What was the SNP position on zonal pricing?

In the early stages of REMA, SNP ministers were relatively honest. Giving evidence to the Scottish Parliament’s Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee on 9th May 2023, Neil Gray, then the Cabinet Secretary for Energy, was asked about the government’s position on zonal pricing. This is what he said:9https://x.com/staylorish/status/1656325388287582212?s=46&t=y9v1mXDn2DQJqjCpgZcKXg

“We are continuing to discuss that with UK ministers. The Scottish Government judges that both suggestions—a nodal pricing system and a zonal pricing system—have potential to disadvantage generators in Scotland because Scottish supply often outstrips demand in each area. We are concerned about the risks for generators. At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that, if the systems are designed well, they may have corresponding benefits for consumers, including business consumers.”

Notice that he foregrounds “risks for generators”.

But once Greg Jackson (the CEO of Octopus Energy) started making waves with his rhetoric about zonal pricing giving Scotland the cheapest electricity in Europe, the SNP sensed an opportunity: it could argue that Westminster was dragging its feet and denying Scottish households cheaper bills. Kate Forbes, in particular, enthusiastically promoted this narrative.10https://x.com/staylorish/status/1916516702545736024?s=46&t=y9v1mXDn2DQJqjCpgZcKXg

However, as we’ve already established, Greg Jackson’s rhetoric was misleading. This is not to say that there weren’t good arguments for zonal pricing - there were. But Greg Jackson had oversold the benefits to Scottish consumers.

Kate Forbes was happy to push the Greg Jackson line. But she must have known the Scottish Government was lobbying against it.

But as the REMA process approached its conclusion both Gillian Martin11https://x.com/staylorish/status/1900147439283150917?s=46&t=y9v1mXDn2DQJqjCpgZcKXg (the Cabinet Secretary for Energy) and Kate Forbes12https://x.com/staylorish/status/1917226050951745693?s=46&t=y9v1mXDn2DQJqjCpgZcKXg began to acknowledge that the Scottish Government was opposed to zonal pricing.

Why was the SNP opposed to zonal pricing?

Recall the SNP position on transmission charging: it wants the claw back of constraint payments to Scottish wind farm revenues to be reduced.

And consider what opposition to zonal pricing means: continued constraint payments and higher revenues for Scottish wind farms.

In both cases, the SNP position is the same as the lobbying position of the big energy companies operating in Scotland.

We have established that if you want to sensibly mitigate the problem of curtailed wind output in Scotland, you need to do one thing or the other: you need to either stop paying so much to compensate for curtailment, or to substantially claw back those payments via transmission charging.

To be against both solutions is perfectly understandable as a corporate lobbying position - energy companies are looking out for their own bottom line.

But to be against both of those solutions as a government is a fundamentally incoherent and unserious position. The SNP wants higher profits for Scottish wind farms, and cheaper bills for Scottish households. Good luck making sense of that.

The irony of SNP complaints about the GB electricity market is that the most dysfunctional aspects of the market - payments to Scottish wind farms to sit idle, and inadequate claw back of those payments via transmission charging - are things the SNP wants to keep.

Please log in to create your comment